I chose Ernest Hemingway because he is deeply out of fashion, still over-admired by the literary boys-with-toys brigade, still shunned by women readers put off by the macho myth. His style is wrongly thought to be both simple and imitable; it is neither. His novels are better known than his stories, but it is in the latter that his genius shows fullest, and where his style works best. I deliberately didn't choose one of the famous stories, or anything to do with bullfighters, guns or Africa. “Homage to Switzerland” is a quiet, sly, funny story (Hemingway's wit is also undervalued) which also — rarely — is formally inventive. It has a three-part, overlapping structure, in which three Americans wait at different Swiss station cafés for the same train to take them back to Paris. Each man plays games of the sort a moneyed and therefore powerful expatriate is tempted to play with the nominally subservient locals — waitresses, porters, and a pedantic retired academic. But as the story develops, it's clear that social power and moral power are not on the same side. I hope “Homage to Switzerland” will make you forget the swaggering “Papa” Hemingway of myth, and hear instead the truthful artist.

I got to wondering: is Hemingway out-of-fashion? Which circles would I have to travel in to know? I still love Hemingway — there are at least two-dozen short stories I’m very fond of (including “Homage”) and even a novel (The Sun Also Rises). I’m also familiar with Hemingway-induced dis-ease, particularly when it comes to The Sun Also Rises. The patent anti-Semitism cannot be overlooked; it’s a rotten impulse, to say the least, but Hemingway indulges it to deliberately position the Abrahamic religious-moral code as obsolete and vexatious. It’s the same code, of course, that provides the framework for Christianity and Islam, but it was the current norm to pick on the Jews — an easy and “acceptable” target. Hemingway sometimes had trouble resisting the easy target.

So, yes: loving Hemingway does take effort.

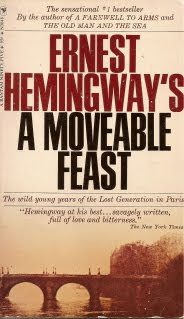

But love him I do. Recently, at the village thrift shop, I discovered (beneath a pile of Dan Browns) a copy of A Moveable Feast. It’s small enough to fit in my purse, a book made for travel and short exposure to the page. On Saturday as the women in my family bravely forged through the Ottawa crowds to catch a glimpse of Will and Kate, I sat in the shady patio of a café, swigged an iced coffee and lingered over the prose.

But love him I do. Recently, at the village thrift shop, I discovered (beneath a pile of Dan Browns) a copy of A Moveable Feast. It’s small enough to fit in my purse, a book made for travel and short exposure to the page. On Saturday as the women in my family bravely forged through the Ottawa crowds to catch a glimpse of Will and Kate, I sat in the shady patio of a café, swigged an iced coffee and lingered over the prose.Then there was the bad weather. It would come in one day when the fall was over. We would have to shut the windows in the night against the rain and the cold wind would strip the leaves from the trees in the Place Contrescarpe. The leaves lay sodden in the rain and the wind drove the rain against the big green auto-bus at the terminal and the Café des Amateurs was crowded and the windows misted over from the heat and the smoke inside. It was a sad, evilly run café where the drunkards of the quarter crowded together and I kept away from it because of the smell of dirty bodies and the sour smell of drunkenness. The men and women who frequented the Amateurs stayed drunk all of the time, or all of the time they could afford it, mostly on wine which they bought by the half-liter or liter. Many strangely named aperitifs were advertised, but few people could afford them except as a foundation to build their wine drunks on. The women drunkards were called poivrottes which meant female rummies.

Hemingway situates the Café des Amateurs as a literal cesspool in the lowest aspect on the rue Cardinal Lemoine. He describes the effect the bad weather has on an already unfortunate scene, making subtle reference to his anxieties as a young man who is all but fleeing this dismal locale. The young Hemingway finally comes to “a good café that I knew on the Place St.-Michel.

It was a pleasant café, warm and clean and friendly, and I hung up my old waterproof on the coat rack to dry and put my worn and weathered felt hat on the rack above the bench and ordered a café au lait. The waiter brought it and I took out a notebook from the pocket of the coat and a pencil and started to write. I was writing about up in Michigan and since it was a wild, cold, blowing day it was that sort of day in the story. I had already seen the end of fall come through boyhood, youth and young manhood, and in one place you could write about it better than in another. That was called transplanting yourself, I thought, and it could be as necessary with people as with other sorts of growing things. But in the story the boys were drinking and this made me thirsty and I ordered a rum St. James. This tasted wonderful on the cold day and I kept on writing, feeling very well and feeling the good Martinique rum warm me all through my body and my spirit.

The older Hemingway, the rummy alcoholic fixated with medical photos of distended livers, now nearing the self-appointed end of his life, sees how desperately we fail to connect ourselves correctly to the narrative at hand.

A girl came in the café and sat by herself at a table near the window. She was very pretty with a face fresh as a newly minted coin if they minted coins in smooth flesh with rain-freshened skin, and her hair was black as a crow’s wing and cut sharply and diagonally across her cheek.

I looked at her and she disturbed me and made me very excited. I wished I could put her in the story, or anywhere, but she had placed herself so she could watch the street and the entry and I knew she was waiting for someone. So I went on writing.

The story was writing itself and I was having a hard time keeping up with it. I ordered another rum St. James and I watched the girl whenever I looked up or when I sharpened the pencil with a pencil sharpener with the shavings curling into the saucer under my drink.

I’ve seen you, beauty, and you belong to me now, whoever you are waiting for and if I never see you again, I thought. You belong to me and all Paris belongs to me and I belong to this notebook and this pencil.

Then I went back to writing and I entered far into the story and was lost in it. I was writing it now and it was not writing itself and I did not look up nor know anything about the time nor think where I was nor order any more rum St. James. I was tired of rum St. James without thinking about it. Then the story was finished and I was very tired. I read the last paragraph and then I looked up and looked for the girl and she had gone. I hope she’s gone with a good man, I thought. But I felt sad.

I closed up the story in the notebook and put it in my inside pocket and I asked the waiter for a dozen portugaises and a half-carafe of the dry white wine they had there. After writing a story I was always empty and both sad and happy, as though I had made love, and I was sure this was a very good story although I would not know truly how good until I read it over the next day.

Reading Hemingway isn’t difficult. In fact, it’s deceptively easy, which is one of his fundamental pleasures. There’s no shortage of writers who intimidate the reader, not just from reading the rest of their book, but also from approaching the blank page and pencil to commit to their own stories. But not Hemingway. Hemingway makes a reader feel like writing — a reader like Julian Barnes, certainly. And a reader like me.

3 comments:

WP, Excellent post. Have you, by chance, seen "Midnight in Paris" yet? I've been off of Mr. Allen a while; this movie may just bring me back in. Light fare, yes, but the ideas behind the story were interesting. Corey Stull as Hemingway was fabulous as was the gorgeous First Lady of France, Carla Bruni. Owen Wilson was solid, surprisingly so, and Rachel McAdams was a disappointment, surprisingly so.

.....and the cinematography was, of course, fantastic.

But, the main reason I brought the movie up was the inclusion of Ernest Hemingway as a character. He speaks well for the craft.

Hooray for Hemingway! He's fantastic. I must have read A Moveable Feast six billion times, first all at once, and now I go back and open it randomly to read passages whenever the book catches my eye on the shelf.

Also, hooray for Julian Barnes. I'd never thought about it, but the prose of Arthur & George has a strange similarity to Mr. Hemingway's.

Cxx

http://desoeufs.wordpress.com

DV - argh. No, I have not yet seen MIP, a movie which very much appeals to me. The movies this summer have been difficult to navigate, for various reasons. It looks like I'll be waiting for the DVD release (BTW: I wasn't aware that the singing First Lady Of France made an appearance. Apparently Woody still has French cache!)

do - Nice blog! Also interesting to hear your thoughts about Arthur & George, a book that's on my "to-read" shelf.

Post a Comment