“We’ve got a campaign going on in Ty’s* basement. Care to join us?”

Thus began, in the summer of ’80, my exceedingly brief history with Dungeons & Dragons. I was 15 years old, and getting ready to spend a few weeks at my aunt and uncle’s farm, where my activities would be chiefly devoted to practical concerns. A summer afternoon in a friend’s basement playing this game with the weird name seemed like a good stepping-off point.

Ron, the friend who made the invite, was a Tolkien buff who made my enthusiasm for Lord Of The Rings look like the superficial acquaintance it was. The basement “campaign room” was standard-issue 70s rec room: ceiling-mounted flourescent lighting, inexpensive paneling on the walls, shag rug, a beaten-up couch set and a stocked bar we were too mindful to abuse. Ty was “Dungeon Master” and spread his charts and sheets on the coffee table, which he sequestered to himself so that we couldn’t cheat.

As the graph paper and bizarrely-shaped die were produced, Ty explained the temporary character I was going to play. He might as well have spoken Japanese — or Elvish — the way he droned on. “You’ll catch on as you play,” he said.

It took a while. Ron showed me

the map he'd drawn of the dungeon we were in. There seemed to be a lot of white space. “This is as far as we've got,” he said, pointing to a square. Earlier in the campaign he and some others had encountered and fought orcs, a gang of bandits, and some goblins. “Right now we're in a large room where the only item of consequence is a large tapestry hanging on the eastern wall.” He looked at Ty. “Can we remove the tapestry? Roll it up and take it with us?”

Ty shook his head. “You cannot.”

Ron asked about a few other techniques, including casting a spell of some sort. Ty wasn't budging on the tapestry. Ron huffed. “Alright, try this: with my lance, I gently lift the southeast corner of the tapestry and peer behind it.”

“You see a brick wall.”

“Is there a door, or some hidden panel?”

“All you see is a brick wall.”

“Ahm . . . have I got enough magic left to check for enchantments?”

“Yep.”

“Okay, then.”

“Still a brick wall.”

“Are you serious? What happens if I scratch the tapestry with the point of my lance?”

“Sorry, did you say you slash the tapestry?”

Ron's eyes lit up. “Is this a prompt?”

Ty retreated. “Clarification. I'm just asking.”

Ron leaned forward. “I slash the tapestry!” He made a sweeping motion with his hands.

Ty snickered. “A green, viscous ooze pours out of the slash, covering you and your party and killing you. Your campaign is over.”

This was when the many-sided die finally came into play, to be thrown at Ty the Dungeon Master, who quickly retreated behind the bar.

When tempers finally cooled, another campaign was initiated. The first thing our fictional band encountered was a group of traveling merchants. Once again, the lengthy Q&A. Once again, we might as well have encountered another brick wall. The way I understood it, Ty was a would-be novelist, hoping we'd suss out the plot as we snooped around his setting. To my mind, the obvious encounters in which a central or even secondary character might gain illumination were nothing more than cruel cyphers designed to frustrate players. I said so to my friend as we walked home for supper.

“Well, Ty is a particularly opaque Dungeon Master,” he said. “Ideally we'd have someone a little more generous with his detailing and characterization, like Kent.” Alas, Kent's summer with the Air Cadets had already begun, so the D&D bug never took hold of me.

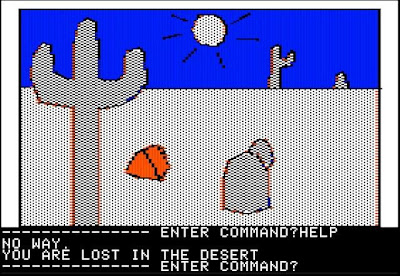

Alright, now take a look at this:

That is a screen from “Wizard & Princess,” one of the earliest Graphic Adventure Games. See the command prompt, and the game response? That's just one example of the moribund stasis these games frequently lapsed into. If you weren't part of a discussion group — which, in this the early age of the telephone modem, would physically gather at the vendors that rented out these games — the odds that you'd ever see these games through to their designed completion were stacked against you. Although I finished one or two of the later, more user-friendly (read: “so simple an addled chimp could do it”) games, I never had the prerequisite patience to engage in the larger, ostensibly more rewarding graphic adventure games.**

No surprise, really, that these games were more robustly enjoyed by my friends who had devoted themselves to the intricacies of D&D. After all, there was

something of value in that tapestry, or behind it, or somehow or other related to it. If we'd only had the patience and the persistence and the correct variation of inquiry we might have discovered just what that was . . . .

Richard Moss entertainingly unspools the quarter-century history of the graphic adventure game, which he reckons has all but concluded — or evolved to a superior format, depending on your point of view — with the advent of episodic games.

*All names have been changed, to protect the guilty.

**Including, most recently, Grim Fandango.