Winnipeg is a decidedly quirky town, and it has dozens of such spots. But it has only one Bridge Drive-In.

“he”/“him” A Canadian Prairie Mennonite from the '70s & '80s, a Preacher’s Kid, slowly recovering from a hemorrhagic stroke. I am not — yet — in a 12-Step Program.

The call woke me up early Satuday morning. Things had been going badly between my friend and his wife. Now he was phoning from a downtown hotel.

I cabbed over. It was a predictably sad business – I was fond of them both, and they were good parents to their kids. But the trajectory their marriage was on had been obvious for some time. There weren't any real surprises, except for the astonishing depth of heartbreak.

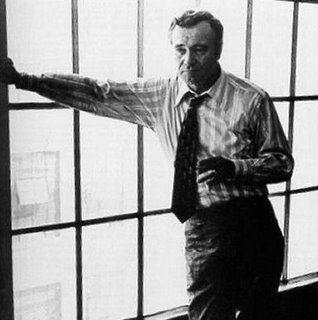

When I got to the hotel room, I took a chair while he tidied up a bit. We talked. I asked a few questions, and mostly listened. Room service came with a Thermos of coffee and some breakfast. The conversation had run its course, so we ate in silence. My friend turned on the TV, and flipped through the channels. One of the movie stations was showing an old Jack Lemmon picture. We stayed put, and watched a few minutes.

Those minutes stretched into the full two hours. When it was over, our mutual silence seemed to have reached a greater depth.

I don't think Save The Tiger sits on any of the “official” Great Movie lists, but today it tops mine. It isn't perfect – Harry Stoner is easily Lemmon's best performance, but he still has moments when he's projecting to the cheap seats; some of the plot contrivances are a little rough around the edges – but even the imperfections bring character to the overall work. It's an unselfconscious time capsule of the early 70s, an era when movie makers didn't mind following a person to work. In Stoner's fashion mill, ironically named after an Italian respite where he recovered from war wounds, Stoner's character is peeled back and exposed to us one layer at a time. He may slouch through most of the movie, but at work his inner steel surfaces, and we see the cunning and ferocity that kept him alive when he was a soldier.

From time to time, he mentions lost ideals, but the only nostalgia that plays convincingly is his nostalgia for big band music and baseball. Stoner isn't trying to negotiate with ideals so much as he's trying to reconnect with his pre-war state of innocence. It is an intensely lonely struggle – Stoner can't invite others to help him with it, because when he does it only magnifies the gap between two solitudes.

The film is bracketed with casualty reports, from Viet Nam, at the beginning, to the injured firemen at film's end. The film makers are sympathetic to Harry's plight, and convincingly communicate why so many business people become antagonistic toward government – it's just one more predator out there, contributing not just to their frustrations, but their demise. “Creative solutions” are a soft-headed indulgence. People are going to get hurt.

This movie is unlikely to stay my number one pick for much longer, but it still belongs there for now. Every life inflicts casualties of its own, and any story, song or movie that takes care to shine a light on the survivor's soul is a welcome work of art. Save The Tiger does, and is, exactly that.

Good grief -- where do I even start? For one thing, This Is Spinal Tap miraculously prolongs one's appreciation of Heavy Metal as an artform. I first saw it -- January 1984, with a Bible School buddy -- in a tiny movie-plex theatre, filled with lads wearing Iron Maiden shirts and Pink Floyd caps. Everyone was laughing and cheering. Spinal Tap wasn't deflating Rock & Roll Mythology -- it was contributing to it.

Christopher Guest has done some incredibly funny movies since then, but Waiting For Guffman doesn't inspire me to join the community theatre, and Best In Show hasn't prompted me to go out and buy a dog. But this "Rockumentary" is different: even as these used-up geezers slip further into a well-deserved obscurity ("Puppet Show! And Spinal Tap"), the urge to actually start a band and take it on the road becomes nearly irresistable. To be so singularly confused and earnest and self-indulgent has to be fun!

Until now, I've avoided talking about DVD bonuses -- I usually equate "extras" with "extra waste of my time" -- but this disc has been packed to the ribs with incredibly entertaining goodies. For one thing, the "audio commentary" is provided by the three surviving Tap members, who take the opportunity to set viewers straight on director Marti DeBergi's "hatchet job". There are also deleted scenes and videos for "Gimme Some Money" "(Listen To The) Flower Children" "Hell Hole" and "Big Bottom" -- all very funny stuff.

I was never one to memorize Monty Python sketches and recite them for the assumed amusement of friends and family, but this movie has brought me as close to that brink as anything done by the Flying Circus. Fortunately, I can resort to timely short-hand: "Take it to eleven!" ("when we need that extra push over the cliff") or "That's just nitpicking, isn't it?" (in response to withering criticism), etc. The surest sign of a replayable movie is its infiltration into the viewer's daily goings-on. And with its ability to straddle that fine line between clever and stupid, This Is Spinal Tap invades with aplomb.

Number three is a particularly difficult choice for me – I could do a top ten Coen Brothers Films list (hmm – note to self...). In a list like that, I'm not sure which would come out on top. Since I have room for only one Coen Brothers title, I'll go with the first movie of theirs that I saw on the big screen: Raising Arizona.

Nicholas Cage's performance as loveable sad-sack H.I. McDunnough (a convenience store hold-up artist who locks his keys in the car) is a comic tour de force. Newcomer Holly Hunter's face switches in an instant from withering scorn, to unshakeable despair. The entire cast is blessed with a script that delivers funny lines to everyone who shows up on set.

And in a film concerned with family and giving birth, the Coens crack their knuckles and roll out one cinematic pun after another. How nasty is it when two brothers deliver themselves from the muddy ground, like demon-spawn? And how pathetic is it when they chose to return on their own accord? And you just know the baddest guy is the biker who carries his own bronzed baby-shoes, and sports a tattoo that reads, “Momma didn't love me.”

It's a funny, dopey movie, and yet when the McDunnoughs finally return the baby to Nathan Arizona and he delivers his cornball consolation speech ("I sure hate to think of Florence leaving me. I do love her so.") I always get choked up. Of course, then he asks the couple to leave the way they came in: by the window.

I was going to include a few juicy quotes that always get me giggling, but there are too many. You can read a few here, or just resign yourself: get the movie off the shelf, drop it in the player, and enjoy.

When a young witch turns 13, it is customary for her to hop aboard her broom, leave home and set herself up in a strange city. On a sunny day, while lying in the tall grass and listening to her transister radio, Kiki decides tonight is the night.

So begins my favourite Hayao Miyazaki movie, Kiki's Delivery Service. Thirteen might seem a little young for a girl to strike out on her own, but as with any Miyazaki movie, there is an innate sense to the proceedings that coheres quite naturally for the viewer. It helps that the world Kiki inhabits has none of the dire threats ours does. And it helps that she's a witch.

It's a little unclear just what a witch's powers amount to, other than broom-flying. Kiki's mother runs a sort of apothecary, and the first snooty witch Kiki encounters claims to be a fortune-teller, before brushing off Kiki and her cat Jiji like so much dandruff. Kiki's chief challenges, it seems, will be social.

Miyazaki's Kiki is the embodiment of youthful energy. Watching her, I reconnect with all the joyous uncertainty that came with leaving my home town. The trick to negotiating these changes is in maintaining confidence in your spirit, and Kiki is one of those blessed youths who doesn't have too many doubts in this regard.

The inevitable does eventually occur: through a series of events, Kiki loses touch with her magic, and her source of confidence. Her spirit seems to reside under a wet blanket; she no longer flies through her life, but walks through it, one miserable step at a time. How she gets back in touch with her magic is a scene that is more momentous and exciting than any of the cliffhanger conclusions we've seen in the last 20 years, because it is deeply emotional and stirringly personal.

I love Miyazaki's work. As with most Japanese anime, Kiki's world is a melange of visual influences. Miyazaki distills a European storybook aesthetic that is at once recognizable and strange. Ivy covers the walls of tall, gabled stone houses, the streets are narrow, trains cut through the countryside and a zeppelin flight is heralded as a big event. All wonderful, but the charm of these images resides in Miyazaki's attention to detail – how many animated movies open with the wind blowing through long grass?

But Miyazaki's originality also lies in his ability to observe and identify so closely with his heroines. I can think of no other living film-maker who cares as deeply about his girl protagonists. Novelist Shusaku Endo has said the Japanese revere their mothers because they exist in sharp counterpoint to their fathers, who are expected to be stern and emotionally distant. Miyazaki seems to follow his muse most closely when he paints the emotional development and dawning maturity of young girls.

Now that I think of it, Miyazaki's characters are almost always in the business of nurturing, though not always in the manner that one expects. But if emotional development comes through encounters with the strange in Castle In The Sky and Spirit World, with Kiki's Delivery Service it comes through finally recognizing what has been there all along.

Film Fave #3

Film Fave #3

There are some directors I’d like to hate, but don’t. Steven Spielberg, for instance – the guy reaches for sentiment whenever an honest conflict of emotion proves too difficult for him to frame. He panders to the crowd, but I usually leave the theatre (or return the DVD) feeling like I got my money’s worth with him. Hey – at least he pandered to me.

Then there are directors I’d love to love, but have trouble doing so. Steven Soderbergh, for instance. The way he takes chances – let’s do a three-hour drama about the drug problem in North America; that book by Stanislaw Lem that Tarkovsky kinda-sorta filmed … any reason why that couldn’t be a smart summer blockbuster?; etc. – is the sort of behavior I naturally tip my hat to. And yet I usually finish a movie feeling as if my patience got tested once too often.

Out of Sight is a good example. Critics were generally impressed with it, and it seemed to signify Soderbergh’s newfound willingness to work with sexy actors and a tight script to deliver a straightforward thriller that should be a hit with audiences. The script was based on an Elmore Leonard novel, and Leonard’s “hip” quotient was growing among Gen X – Soderbergh’s (and my) demographic. So I took my seat and looked forward to a smart guy delivering the sort of smart film that Hollywood habitually dumbed down.

When it was over, I felt residually satisfied, but mostly let down. The story was smart enough, but by the end my interest in its characters had waned. I blamed the actors: George Clooney was still too slick to be taken seriously as a bumbling charmer, and J-Lo was J-Lo (always will be, I'm sure). The gorgeous jaw-dropper falls hard for the gorgeous jaw. Zzzzz.

But, man, did I ever love that opening scene when Clooney storms out of the office, yanks off his necktie and is caught in a mid-throw freeze-frame. That scene had an infectious energy to it, but the freeze-frame was the capper – a quick wink at the audience, to let us know there’d be just enough self-consciousness present to keep this show fun. I sure could stand to see a movie that maintained that stylistic panache right to the film’s conclusion.

The Limey is that movie. Seen laid out on paper, the movie looks like it should be a director’s bloated indulgence: Soderbergh assembles a cast of 60s actors who have since slipped out of the mainstream (Terence Stamp, Peter Fonda, Lesley Ann Warren, Barry Newman, Joe Dallesandro), gets them to sink their teeth into every 60s cliché and hangover you could name, puts them through their paces in a revenge thriller, then skips off to the editing room where he playfully splices up its perspective in a 60s art film style.

Well, it is an indulgence, but it’s one of the leanest and most tightly controlled indulgences I can think of. Take Soderbergh's “art film” splicing: it's a little jarring at first, but it quickly becomes a reliable tone-setter for successive scenes. The first time I saw the film, I thought Soderbergh's narrative play was less intrusive and considerably more effective than Tarantino's had been in Pulp Fiction. With successive viewings each little fragment gains significance, but never in an earth-shaking “So that's what he meant!” way.

As for the acting, it's some of the best you'll see from these veterans of stage and screen. I suspect Soderbergh is an “actor's director”, a guy who gives a few scant instructions, but is mostly inclined to stay out of the way. That would explain why Julia Roberts in a Steven Soderbergh movie is such bad, bad news: she will take over a film, just as surely as Barabara Streisand would. With the exception of Peter Fonda, who was experiencing a bit of a big-screen resurgence at the time, The Limey is cast with actors whose brightest moments have come and gone. They aren't trying to keep their star in the ether; they're trying to do good work. They approach their characters with attention to detail, and project with care.

There is some incredibly satisfying violence, but this is not a graphic film. The script is peppered with snarky asides that reduce me to fits of giggles every time I watch it, but it is surprisingly serious film. The veteran actors all play off roles they became famous for, yet none of it plays self-consciously.

I want to keep gassing on like this, but the plainest truth about this film is its revelations are finally gentle ones – the sort that keep me coming back again and again, because they do not rely so singularly on astonishment and brutal surprise for their impact.

It's a fabulous film that has earned Steven Soderbergh a great deal of cache with me – enough for me to really want to enjoy myself with his next film (if only it weren't Oceans 13!)

Shortly before we moved the b&w TV set to the kitchen, we had it next to my mother's sewing table. A local TV station was broadcasting a week's worth of James Bond movies, and since I was an adolescent and peer discussion was important to me, I asked my parents if I could watch this night's 007 offering. I don't know if my father smirked and gave my mother a broad wink, but he might as well have. "Sure," he said. "Why not?"

My mother's sewing machine was busy that night. I crept closer to the TV, hoping to catch the scurrilous bits between the barrage of electronic interference she threw my way. You would think my quest was a futile business, but no. Somewhere between the zig-zags I caught: a woman in a bikini cuddled next to the titular hero; two gypsy belly-dancers, scratching it out for our hero's affections; a girl in the buff rushing to a hotel bed and slipping between the sheets; our hero with the girl on a train, playing at being husband and wife; our hero, delivering a vicious slap to the girl's jaw ... I dunno. There was some fighting and somesuch in there, too.

It's 30 years later, and I can't get over From Russia With Love. To my mind, this is the Bond movie by which the others are measured, and nearly all of them slip well below the standard -- which is curious, because the movie wears its flaws as if they were badges of honour. The special effects are dodgy (you can spot the string holding up the exploding helicopter), the hero couldn't possibly be more sexist (well ... the early Goldfinger scene in which he gives a massage-girl named "Dink" a swat on the fanny is a bit of a topper), the gypsies come straight from central casting (and do a lousy job of fighting). The knife-in-the-shoe is pretty cool, though, and gets a lot of dramatic mileage.

Connery is called the "dangerous" Bond, and in the early films there's no doubt about it. His character straddles a line between irresistable charm and genuine repugnance. He's like a character from a James Salter story: the cad who crashes the party drunk, helps himself to the cognac, and gives the hostess a pinch. He's appalling, but the hostess can't stop thinking about him. Of course the villains are cold and ruthless; worse still, they have impeccable manners.

Bond struts around these stiffs, the embodiment of loose-limbed, hands-in-the-pockets insouciance. And he flips from adolescent id to parental condescension -- usually after there's been a nasty, protracted fight with a Bond Girl's safety at stake. It's irredeemably bad behaviour, with not a trace of reality to be found.

Enlightened men shouldn't enjoy this stuff -- but some of us do. Consider it our Pretty Woman.

The luau sets itself up as bacchanalia "lite", with bonfires and beer drinkers, and everyone in their bathing suits chasing each other in the sand and behind the bushes, like some Sergio Aragonés cartoon between the frames of MAD Magazine. But despite this clothed-yet-utterly-without-nuance setting -- or, more likely because of it -- the scene is an effectively horny set-piece for Gidget to play out her Shakespearean hi-jinx: persuading Moondoggie to kiss her in the pretense of raising Kahuna's jealousy, then turning tables to further stoke Moondoggie's desire. It backfires terribly, of course, and Gidget finds herself in a nasty state of anxiety and expectation, awaiting (in a white dress on a red couch, fer cryin' out loud!) the older, jaded Kahuna's liquored-up attention.

The luau sets itself up as bacchanalia "lite", with bonfires and beer drinkers, and everyone in their bathing suits chasing each other in the sand and behind the bushes, like some Sergio Aragonés cartoon between the frames of MAD Magazine. But despite this clothed-yet-utterly-without-nuance setting -- or, more likely because of it -- the scene is an effectively horny set-piece for Gidget to play out her Shakespearean hi-jinx: persuading Moondoggie to kiss her in the pretense of raising Kahuna's jealousy, then turning tables to further stoke Moondoggie's desire. It backfires terribly, of course, and Gidget finds herself in a nasty state of anxiety and expectation, awaiting (in a white dress on a red couch, fer cryin' out loud!) the older, jaded Kahuna's liquored-up attention.

"You've taken your first step into a larger world." Obi-Wan Kenobi

There were people in our village who did not go to the movies -- and as a six-year-old, neither did I. The reasoning I frequently heard was, "If the Lord were to return, would you want Him to find you in a theatre?" My parents never used that line, but it was common enough to fall on my ears. I figured the chances of the Lord returning and finding me in a theatre were considerably slimmer than finding me on the toilet (which I considered the more embarrassing situation). Besides, I was told He saw me no matter where I was, so what was the dif?

And so the tiny cinema in the middle of our village represented forbidden fruit. Like Miriam Toews' Nomi, I too asked if I could go see The Swiss Family Robinson with my friends. My mother denied my request, along with enough of my following entreaties for me to get the picture: I wasn't going to see any movies in the town theatre.

Six years later, I stood in front of my father and asked the question again. This time we were in Denver, where my father was working on his doctorate. A friend in the apartment below ours was going to see Star Wars with his father, and I was asked if I wanted to tag along. I didn't know what Star Wars was, but if it was anything like Star Trek, I was in. All I had to do was persuade my father.

He hesitated. I cajoled. He told me to stifle. I did, and slunk off to my bedroom. In the morning, I again broached the subject. He said he'd prayed about it, and felt alright about giving me permission.

I'm slow to hit "post" on this scenario -- who wants to be the holopschi-eating peasant to whom the moving picture show is verboten? Furthermore, my silent justification wasn't nearly so straight-forward or nuanced: I wanted to see the movie, and I wasn't beyond employing a little manipulative sophistry when I had to. In hindsight, as I watch my daughters approach puberty, my father's hesitation doesn't seem altogether absurd. In my case, I'm not as concerned about movie content as I am about internet access. This is how a father worries.

Just before I stepped into my friend's car, my father took me aside and said, "Sometimes, just before the movie starts, the theatre shows an advertisement for another movie in another theatre. If they start showing anything that bothers you, don't worry about it. If you have to, you can just close your eyes and wait for it to be over."

The preview was for A Bridge Too Far. The movie took two years to make, and starred a hundred big names I didn't recognize. Soldiers, jeeps and explosions. It looked incredible.

And then the 20th Century Fox anthem played. Spectacle aside, what did we get? A kid who lives with his uncle and farms sand. Doesn't do anything cool, just wants to get the hell out of Dodge. Gets told his father was a legendary warrior, then embarks on a crazy rescue mission with a swashbuckling pirate and a giant ape. He rescues the princess, blows up the evil fortress and saves the day.

And there was no "spectacle aside". These were special effects nobody -- nobody -- had seen before. Do you think my 12-year-old male adolescent small-town holopschi-eating Mennonite head didn't split open like a freakin' walnut?

"That's no moon -- that's a space station."

So, no: I don't tire of this movie. And there have been stretches in my generally trial-free life when this movie has been, next to the Bible and the one single subject common to the thoughts of all men, the subject I've spent the most time mulling over. I'm not in that headspace anymore, mind you. Five movies later, the verdict is in -- it's the Grade Nine burn-out's attempt at The Lord Of The Rings. The series as a whole is so hobbled with flaws that questions are legitimately raised about the quality of the movie that kicked it into motion.

And that's fine -- that there were only two movies worth watching in the entire series doesn't much bother me. This is the movie that stood on the other side of the threshold and welcomed me into a larger world. And its playful sense of perspective was one of its deepest charms. Luke, Han, Chewy and Leia can sprint all over the Death Star -- this is business as usual. But when they finally come back to their spaceship, they're at a precipice that looks down onto it. This seemingly casual attention to detail brought an unusual depth and dimension to Space Opera, and created precisely the sort of persuasive world a 12-year-old boy could get very excited about.

And when my kids are watching it, I'm usually beside them.

Synchronicitous update: Drawn! links to Ralph McQuarrie's new site (McQ being the guy who deserves the most credit for "inventing" Star Wars)

Synchronicitous update 2: I wish this was canon:

|

| "It's never the same film twice, maaaan!" |