“he”/“him” A Canadian Prairie Mennonite from the '70s & '80s, a Preacher’s Kid, slowly recovering from a hemorrhagic stroke. I am not — yet — in a 12-Step Program.

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Monday, March 29, 2010

The Club Dumas by Arturo Pérez-Reverte

The lovely young lady who sold me this book assured me it was a “wonderful read” but I too often found it tedious and overwrought. The woodcuts, illustrations and tables were the sort of textual interruption I enjoy, and Pérez-Reverte's tangential obsessions with Dumas and forgeries were occasionally interesting. But the alcoholic anti-hero's irresistible charm completely defied my imagination.

Pérez-Reverte relies a great deal on continental romanticism, using baroque settings to supply depth of feeling where his plot and characters cannot. I suspect this book appeals mostly to readers in their 20s, anticipating the joys of their next student EuroRail pass.

Speed-reading quotient: 95% of the book.

Pérez-Reverte relies a great deal on continental romanticism, using baroque settings to supply depth of feeling where his plot and characters cannot. I suspect this book appeals mostly to readers in their 20s, anticipating the joys of their next student EuroRail pass.

Speed-reading quotient: 95% of the book.

Saturday, March 27, 2010

Of Books And Such

I get a kick out of Michelle Kerns: she's got a lot of "get over it & get on with it" sass that makes for refreshing reading about reading. To wit: Book Reviewing As A Bloodsport; The Top 20 Most Annoying Book Review Cliches (Hm. Guilty of the first four, at least); and Book Review Bingo. If any of that tickles you, there's more of same at the sidebar.

Also: Carole Baron (Knopf) makes the case for editors at publishers. Personally, as much fun as self-publishing is, it's the editor I miss the most -- for editing, as much as any of the other fine roles Baron and company provide.

And finally, Michael Blowhard recently pointed me to Writer 2.0, a collection of pros trying to dowse out a financially feasible future for writer-types. It's still early in the (extremely erratic) game, but I like what I see.

Also: Carole Baron (Knopf) makes the case for editors at publishers. Personally, as much fun as self-publishing is, it's the editor I miss the most -- for editing, as much as any of the other fine roles Baron and company provide.

And finally, Michael Blowhard recently pointed me to Writer 2.0, a collection of pros trying to dowse out a financially feasible future for writer-types. It's still early in the (extremely erratic) game, but I like what I see.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Artistic Expression & Age, Plus A Little Self-Help

The first time I saw a display of Monet paintings I was surprised by my emotional response. The early-to-mid-career paintings provoked in me a peevish distaste that bordered on disgust: those hazy water lillies, the primly dressed aristocratic ladies with their sprats in tow, all glazed-over with Monet's forgiving soft-focus approach . . . feh. I stopped short, however, when I reached the haystacks. The vibrancy, the urgency of expression caught me and kept me rooted to the spot.

The haystacks were later Monet, of course, painted in moments of high fever when he seemed convinced he hadn't any time to spare on his usual finishing gimmicks in the studio.

The haystacks were later Monet, of course, painted in moments of high fever when he seemed convinced he hadn't any time to spare on his usual finishing gimmicks in the studio.

The haystacks were later Monet, of course, painted in moments of high fever when he seemed convinced he hadn't any time to spare on his usual finishing gimmicks in the studio.

The haystacks were later Monet, of course, painted in moments of high fever when he seemed convinced he hadn't any time to spare on his usual finishing gimmicks in the studio. Robert Cohen takes note of a similar shift in perspective in aging writers. In this essay for The Believer Cohen begins with Thomas McGuane, “a recovering 'word drunk' by his own admission — [speaking of] how the experience of his middle years, which among other things consisted of attending a great many funerals, affected not just the substance of his work but its tones and its rhythms too.

'As you get older,' he advises, 'you should get impatient with showing off in literature. It is easier to settle for blazing light than to find a language for the real. Whether you are a writer or a bird-dog trainer, life should winnow the superfluous language. The real thing should become plain. You should go straight to what you know best . . . . you want something that is drawn like a bow, and a bow is a simple instrument. A good writer should get a little bit cleaner and probably a little bit plainer as life and the oeuvre go on.'For all its plain good sense, this seems a fairly radical sentiment. Generally we secular types resist the imperative-prescriptive mode: we don’t like being told what’s real and what’s true and what we should or shouldn’t do. But McGuane’s shoulds here are instructive. He doesn’t concede for argument’s sake that such notions as truth and 'the real' may not exist, may be only quaint premodern artifacts, tarnished if not shattered after decades of rough handling by lawyers, humanities professors, and people with French surnames. No, a Westerner’s impatience with that sort of dithering and equivocal epistemological bullshit — with all bullshit — makes its own point: namely, that if experience (and for experience we might go ahead and substitute the word death) teaches us what’s real and what isn’t, then to pretend otherwise, either in substance or in aesthetic form, is an evasion, a shirking of the writer’s responsibility to truth. The rest is commentary.”

There are other directions aging writers take. Cohen's survey is fairly catholic in its content, and surprisingly moving by conclusion. You can read it here.

In fact, I found last month's issue of The Believer made for particularly satisfying reading: Andrea Richards' evocative exploration of her late, eccentric uncle's library of esoterica; Casey Walker's personal re-examination of one of William T. Vollmann's obsessive existential howls; the interview with Trent Reznor — all delivered in The Believer's signature gentle enthusiasm, and highly recommended.

Tangentially related: Chuck Pahlaniuk offers up a pertinent self-help regime here.

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Guitars I Dig: "Trigger"

Preacher Dan's delight in a recent Willie Nelson concert got me thinking. It's time to introduce a new category for this blog: Guitars I Dig.

The inaugural guitar is none other than Nelson's beloved, and extremely well-used, "Trigger."

Here is the wiki. The notation concludes with Nelson's quip that he'll retire when Trigger finally falls apart. Given his carpal tunnel troubles, there may well be some gravitas to that statement. I hope not. I'd rather the man and his guitar deliver music for years to come.

If you want your own "Trigger," Martin made a limited edition replica in 1999: The N-20WN. You'll have to do the eBay thang, I guess. And good luck: this one had an asking price of $3,800.

BTW, a Willie Nelson guitar performance is well worth seeing, even on DVD. His styling is always unique, even occasionally, I daresay, bizarre.

The inaugural guitar is none other than Nelson's beloved, and extremely well-used, "Trigger."

Here is the wiki. The notation concludes with Nelson's quip that he'll retire when Trigger finally falls apart. Given his carpal tunnel troubles, there may well be some gravitas to that statement. I hope not. I'd rather the man and his guitar deliver music for years to come.

If you want your own "Trigger," Martin made a limited edition replica in 1999: The N-20WN. You'll have to do the eBay thang, I guess. And good luck: this one had an asking price of $3,800.

BTW, a Willie Nelson guitar performance is well worth seeing, even on DVD. His styling is always unique, even occasionally, I daresay, bizarre.

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

Avatar & Films For Adults

I recently said my Academy vote for Best Picture would have gone to Up In The Air, because it offered "the most adult pleasures" of the nominees I'd seen -- a summary begging to be taken wildly out of context. What I meant was, out of the films nominated Up In The Air far and away generated the most dinnertime conversation among the adults in my social circle. I've not yet seen An Education, which I suspect was Up In The Air's closest rival (by my reckoning). Precious certainly elicited shudders. And the Coen Brothers and Tarantino have the sort of personality that generates controversy, if not always the sort of movie that sticks to your ribs.

But Up? District 9? The Hurt Locker? Even if you luuuuuuuuurved those movies, what was there to say about them afterwards? These movies asked the questions on behalf of the audience, and then they marched on and answered them, too. As for Avatar, what is there to discuss about a pale imitation of Princess Mononoke -- minus the depth of character, the moral ambiguities, the persuasively recognizable "otherness" of the mythic setting?

Quite a bit, apparently. There's the Ayahuasca connection, for wide-eyed anthro-types. Then there's this, by James Bowman.

Time to re-set the dinner table.

But Up? District 9? The Hurt Locker? Even if you luuuuuuuuurved those movies, what was there to say about them afterwards? These movies asked the questions on behalf of the audience, and then they marched on and answered them, too. As for Avatar, what is there to discuss about a pale imitation of Princess Mononoke -- minus the depth of character, the moral ambiguities, the persuasively recognizable "otherness" of the mythic setting?

Quite a bit, apparently. There's the Ayahuasca connection, for wide-eyed anthro-types. Then there's this, by James Bowman.

Time to re-set the dinner table.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

The Comic Book Store

We had a ringette game in the city last Friday. En route to the arena I spotted a small comic book store I'd visited a few years earlier. I was astonished to see it was still open for business: I'd originally paid it a visit during the day, and was the sole customer. The guy who ran the place was approachable, and had a gentle enthusiasm for his product that wasn't too hard to take. At the time I noticed that nearly every major Marvel storyline was written by Ed Brubaker. I asked if this was a case of Brubaker really being that good, or the rest of Marvel's stable being pathetic. This opened the floodgates, but the short answer was, “Yes.” I left an hour later with a few choice collections, but wondered how much longer this place could survive.

One of my weekly blog-visits is Valerie D'Orazio's Occasional Superheroine (hat-tip to JS). When D'Orazio announced a forthcoming gig as writer for a Punisher one-off, I made a mental footnote to look into it. Now, here we were, with this store still very much in business. I asked my daughter if she'd mind stopping for a quick visit. She said no, so in we went.

With both of my daughters in adolescence stores now fall into two categories: 1) the kind where I find a chair while the girls dive in; 2) the kind where the daughters stick to their father's side like a pair of extra ribs, because the only subject of interest is When can we get out of here? Even though the girls can spend hours poring over comics at home, the comic book store fell decidedly into the latter category.

First of all, the place was packed.

People milled about the racks, the air was raucous with boisterous conversation, and the guy I'd originally met danced from clique to clique. “Hey, you're new!” He skipped over as we crossed the threshold. “If you have any questions about anything you see, just ask me. I read everything that comes in!” I thanked him, but he was already gone, keen to interject a personal observation into a discussion regarding the discrepancies between the novels and on-line dynamics of World of Warcraft. I forged through the crowds, with my daughter following close behind.

For all the talk of on-line gaming, there was a distinct absence of internet technology. I saw one Blackberry in use, but other than that, nothing. I noticed an open door revealing a plain white room illuminated by fluorescent lights, furnished with folding tables and chairs. I took a closer look, expecting to see laptops or computer monitors. Instead there were companies of guys playing an elaborate card game (Magic, from the looks of it). I moved back to the racks, found what I was looking for, then bought it and left.

When we reached a discreet distance from the shop, I said, “Did you notice anything about that place?”

My daughter shrugged. “Like what?”

“Like, you were the only girl there.”

“Well, I noticed that.”

“Did you notice anything about the guys in there?”

“Like what?”

I shook my head and sighed. “Your grandmother used to worry I'd take up permanent residency there.”

One of my weekly blog-visits is Valerie D'Orazio's Occasional Superheroine (hat-tip to JS). When D'Orazio announced a forthcoming gig as writer for a Punisher one-off, I made a mental footnote to look into it. Now, here we were, with this store still very much in business. I asked my daughter if she'd mind stopping for a quick visit. She said no, so in we went.

With both of my daughters in adolescence stores now fall into two categories: 1) the kind where I find a chair while the girls dive in; 2) the kind where the daughters stick to their father's side like a pair of extra ribs, because the only subject of interest is When can we get out of here? Even though the girls can spend hours poring over comics at home, the comic book store fell decidedly into the latter category.

First of all, the place was packed.

|

| Kinda like this. |

For all the talk of on-line gaming, there was a distinct absence of internet technology. I saw one Blackberry in use, but other than that, nothing. I noticed an open door revealing a plain white room illuminated by fluorescent lights, furnished with folding tables and chairs. I took a closer look, expecting to see laptops or computer monitors. Instead there were companies of guys playing an elaborate card game (Magic, from the looks of it). I moved back to the racks, found what I was looking for, then bought it and left.

When we reached a discreet distance from the shop, I said, “Did you notice anything about that place?”

My daughter shrugged. “Like what?”

“Like, you were the only girl there.”

“Well, I noticed that.”

“Did you notice anything about the guys in there?”

“Like what?”

I shook my head and sighed. “Your grandmother used to worry I'd take up permanent residency there.”

Punisher MAX: Butterfly, by Valerie D'Orazio, art by Laurence Campbell

John Updike, grousing about Don DeLillo, famously said, “The trouble with a tale where anything can happen is that somehow nothing happens.” Nowhere is this observation truer than in the field of comic books — surely a medium in which nearly anything could happen. It is disappointingly rare for a reader to encounter a genuinely playful intelligence at work; rarer still in the über-dreary Punisher franchise. What an astonishment, then, to encounter Butterfly, a one-shot written by Valerie D'Orazio, a short narrative so layered, twisted and personally invested it blows apart genre conventions and reassembles them in a way that opens the field to manifest possibilities.

“Butterfly” presents herself to a potential publisher as a “mob hit-woman” keen to expose all in her memoirs. On the face of it, she and her story bear more than a passing resemblance to The Punisher. But as the truths behind the story she's peddling unfold, then fold in again in increasingly complex patterns, his presence becomes increasingly ominous.

D'Orazio and her artist co-conspirator Laurence Campbell take on a number of modern comic tropes, including, particularly, Frank Miller's noir fabulism. But they don't just tweak and play off the genre's abundant ironies, they exploit them to spectacular effect. To choose just one non-spoiler example, after decades of establishing a “Movie Of The Month” approach to controversial subject matter, Butterfly marks the first time that the emotional effects of child abuse are trenchantly disclosed, in a way that is absolutely integral to the narrative engine of the book.

Nuff said — buy the book and discover its many pleasures for yourself. And here's hoping Butterfly ignites a much-needed revolution in a genre where so little seems to truly happen.

“Butterfly” presents herself to a potential publisher as a “mob hit-woman” keen to expose all in her memoirs. On the face of it, she and her story bear more than a passing resemblance to The Punisher. But as the truths behind the story she's peddling unfold, then fold in again in increasingly complex patterns, his presence becomes increasingly ominous.

D'Orazio and her artist co-conspirator Laurence Campbell take on a number of modern comic tropes, including, particularly, Frank Miller's noir fabulism. But they don't just tweak and play off the genre's abundant ironies, they exploit them to spectacular effect. To choose just one non-spoiler example, after decades of establishing a “Movie Of The Month” approach to controversial subject matter, Butterfly marks the first time that the emotional effects of child abuse are trenchantly disclosed, in a way that is absolutely integral to the narrative engine of the book.

Nuff said — buy the book and discover its many pleasures for yourself. And here's hoping Butterfly ignites a much-needed revolution in a genre where so little seems to truly happen.

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

Tuesday, March 09, 2010

David Denby Dissects My Mother's Favorite Movie Director

Actually, I can't state with absolute certainty that Clint Eastwood is my mother's favorite director. But in our last few phone conversations she has made mention of how Eastwood manages to bring pleasant surprises to the movies she watches. Even after reading David Denby's analysis of Clint Eastwood, I still consider Eastwood a mostly above average filmmaker. But that capacity to surprise is well demonstrated (and documented), and makes Eastwood someone worth keeping an eye on.

Monday, March 08, 2010

Post-Oscars Commentary

And the award for Best Post-Oscars Commentary goes to ... David Edelstein, for his bitchy blog entry, "Breaking News! District 9 Wins Best Picture!" -- here. Want a quote? Let's see, let's see: there are so many wicked take-downs and back-handed compliments to choose from, but I think I'll go with ... this:

"As someone whose life wasn’t changed by the films of John Hughes (except that I suddenly had to listen to a lot more shitty rock songs in movies), I was struck by the emotional intensity that came through even in those brief snippets of his work."

Coincidentally, I missed the bulk of the Oscars because I was finally getting round to watching District 9 (the opportunity presented itself, so I seized it). Of the Best Picture options, I say D9 was the most intense, funny and depressing of the lot (although I haven't yet seen A Serious Man or An Education). Were I a member of the Academy, my vote probably would have gone to Up In The Air, because it offered the most adult pleasures of the bunch. But another Cameron win would have been difficult to choke down, so I do not begrudge Ms. Bigelow.

Tangentially related: I figure John Travolta begins and ends each day by getting down on his knees and thanking L. Ron Hubbard for Quentin Tarantino. Now I'm wondering if Quentin might not be doing the same, regarding Christoph Waltz.

"As someone whose life wasn’t changed by the films of John Hughes (except that I suddenly had to listen to a lot more shitty rock songs in movies), I was struck by the emotional intensity that came through even in those brief snippets of his work."

Coincidentally, I missed the bulk of the Oscars because I was finally getting round to watching District 9 (the opportunity presented itself, so I seized it). Of the Best Picture options, I say D9 was the most intense, funny and depressing of the lot (although I haven't yet seen A Serious Man or An Education). Were I a member of the Academy, my vote probably would have gone to Up In The Air, because it offered the most adult pleasures of the bunch. But another Cameron win would have been difficult to choke down, so I do not begrudge Ms. Bigelow.

Tangentially related: I figure John Travolta begins and ends each day by getting down on his knees and thanking L. Ron Hubbard for Quentin Tarantino. Now I'm wondering if Quentin might not be doing the same, regarding Christoph Waltz.

Saturday, March 06, 2010

Point Omega by Don DeLillo

Is there an artist, or any sort of craftsperson, who doesn't suspect that the real work is being done in a medium not their own? I know a cabinet maker who wishes he were more adept at metals or plastics. Unfortunately for him, wood is what gets him the awards — and money. Actors want to be directors. T Bone Burnett envies painters, while Ry Cooder's admiration for novelists is such that, last I heard, he let Michael Ondaatje talk him into quitting his day job and picking up the fountain pen. As for me, I doubt anyone's come closer to the Platonic Ideal than Hank Williams or Donald Fagen.

Don DeLillo has a jones for anyone in the visual arts. His male protagonists get the hots for sculptors (Americana), photographers (Mao II) and painters (Underworld). In Point Omega (A) a filmmaker tries to woo a “defense intellectual,” a blowhard tangentially responsible for Iraq, to submit to the camera. This time the would-be suitors are both male, while the intellectual's daughter shows up to provide the merest frisson of heterosexual tension.

But if the bulk of PO's text is any indication, the central tension in the narrative originates in an actual “film installation” by Douglas Gordon entitled 24 Hour Psycho. The installation involves projecting Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho slowed down to the point where it can only be seen in its entirety over a course of 24 hours. The characters in this short novel react a great deal to this installation, but — po-mo irony at work here — no-one so much as DeLillo himself.

“I talked to them one day about war. Iraq is a whisper, I told them. These nuclear flirtations we've been having with this or that government. Little whispers,” he said. “I'm telling you, this will change. Something's coming. But isn't this what we want? Isn't this the burden of consciousness? We're all played out. Matter wants to lose its self-consciousness. We're the mind and heart that matter has become. Time to close it all down. This is what drives us now.”

PO's central concern, then, is this business of the best and worst that human consciousness can achieve, and what happens when it finally gets obliterated. Any craftsperson will tell you many of the most precious stretches of life are when self-consciousness dissipates, those times when a person gets so preoccupied with the task at hand — with craft — that she forgets herself.

When I picked up the book I thought 100 pages of this sort of “pushing at the fabric” was probably about right. By page 75 it felt too long. I had fewest difficulties with the central third of the book, where the filmmaker hangs out with the intellectual and his daughter in a desert retreat. The three exist as an unholy po-mo Trinity, hoping to cook up and project something as they stew in each other's proximity. When the daughter disappears, I found it a truly haunting moment that quite properly shocked the two surviving posers. But when the entire enterprise swung exclusively to 24 Hour Psycho, I switched gears and sped-read to the conclusion.

I am an admirer of DeLillo — as dry and remote as his prose can seem, I can't help but see his fiction as being almost embarrassingly personal in concern, and nowhere moreso than in Mao II. The author's duty is to enthrall, and DeLillo has done that for me by exploring what abstractions like “forces of history” (A) mean in their most personal sense. When DeLillo himself became an abstraction — “internationally feted novelist” — he wrote this passage, which I read as DeLillo's own Point Omega.

Camus said, “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide.” Most days I can snicker and say, “Only if you don't have to shop for bananas.” Those are the days I'll tell you DeLillo's most recommended work is Pafko At The Wall, his magnum opus Underworld, his most harrowing work Mao II. The days when I can't snicker are the days when I am simply grateful that DeLillo has attended to self-argument, internal dissent — the democratic shout. The Novel.

Don DeLillo has a jones for anyone in the visual arts. His male protagonists get the hots for sculptors (Americana), photographers (Mao II) and painters (Underworld). In Point Omega (A) a filmmaker tries to woo a “defense intellectual,” a blowhard tangentially responsible for Iraq, to submit to the camera. This time the would-be suitors are both male, while the intellectual's daughter shows up to provide the merest frisson of heterosexual tension.

But if the bulk of PO's text is any indication, the central tension in the narrative originates in an actual “film installation” by Douglas Gordon entitled 24 Hour Psycho. The installation involves projecting Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho slowed down to the point where it can only be seen in its entirety over a course of 24 hours. The characters in this short novel react a great deal to this installation, but — po-mo irony at work here — no-one so much as DeLillo himself.

“I talked to them one day about war. Iraq is a whisper, I told them. These nuclear flirtations we've been having with this or that government. Little whispers,” he said. “I'm telling you, this will change. Something's coming. But isn't this what we want? Isn't this the burden of consciousness? We're all played out. Matter wants to lose its self-consciousness. We're the mind and heart that matter has become. Time to close it all down. This is what drives us now.”

PO's central concern, then, is this business of the best and worst that human consciousness can achieve, and what happens when it finally gets obliterated. Any craftsperson will tell you many of the most precious stretches of life are when self-consciousness dissipates, those times when a person gets so preoccupied with the task at hand — with craft — that she forgets herself.

When I picked up the book I thought 100 pages of this sort of “pushing at the fabric” was probably about right. By page 75 it felt too long. I had fewest difficulties with the central third of the book, where the filmmaker hangs out with the intellectual and his daughter in a desert retreat. The three exist as an unholy po-mo Trinity, hoping to cook up and project something as they stew in each other's proximity. When the daughter disappears, I found it a truly haunting moment that quite properly shocked the two surviving posers. But when the entire enterprise swung exclusively to 24 Hour Psycho, I switched gears and sped-read to the conclusion.

I am an admirer of DeLillo — as dry and remote as his prose can seem, I can't help but see his fiction as being almost embarrassingly personal in concern, and nowhere moreso than in Mao II. The author's duty is to enthrall, and DeLillo has done that for me by exploring what abstractions like “forces of history” (A) mean in their most personal sense. When DeLillo himself became an abstraction — “internationally feted novelist” — he wrote this passage, which I read as DeLillo's own Point Omega.

Camus said, “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide.” Most days I can snicker and say, “Only if you don't have to shop for bananas.” Those are the days I'll tell you DeLillo's most recommended work is Pafko At The Wall, his magnum opus Underworld, his most harrowing work Mao II. The days when I can't snicker are the days when I am simply grateful that DeLillo has attended to self-argument, internal dissent — the democratic shout. The Novel.

Thursday, March 04, 2010

Listening To The (Movie) Crickets

The precious few movie critics still on a payroll are watching the axe swing ever closer, and plaintively making their case. Thomas Doherty's argument is a variation on "Teh Interwebz iz maakng us stoopid" while Richard Schickel argues that ... well, frankly, whatever point Richard was trying to make was obliterated by my concern that his GP get the dosages right. Schickel's earlier argument was more cogent, and I replied to it, here.

The core concern remains largely unstated by these people. Culture critics must surely be the most optimistic and subtle group of people you could hope to encounter, because the question that dares not speak its intent is, "Am I going to get paid for this?" One answer occurs to the only surviving critic-at-large: as ever, the tech-savvy and fiscally-minded Roger Ebert leads the pack when it comes to innovative commercial/critical enterprise.

Ebert does it because he can, and God love 'im for it. As for the others, who can say? Perhaps it's not too late for a Luddite colony.

The core concern remains largely unstated by these people. Culture critics must surely be the most optimistic and subtle group of people you could hope to encounter, because the question that dares not speak its intent is, "Am I going to get paid for this?" One answer occurs to the only surviving critic-at-large: as ever, the tech-savvy and fiscally-minded Roger Ebert leads the pack when it comes to innovative commercial/critical enterprise.

Ebert does it because he can, and God love 'im for it. As for the others, who can say? Perhaps it's not too late for a Luddite colony.

MAO II, Don DeLillo

“Even if I could see the need for absolute authority, my work would draw me away. The experience of my own consciousness tells me how autocracy fails, how total control wrecks the spirit, how my characters deny my efforts to own them completely, how I need internal dissent, self-argument, how the world squashes me the minute I think it's mine.”

He shook out a match and held it.

“Do you know why I believe in the novel? It's a democratic shout. Anybody can write a great novel, one great novel, almost any amateur off the street. I believe this, George. Some nameless drudge, some desperado with barely a nurtured dream can sit down and find his voice and luck out and do it. Something so angelic it makes your jaw hang open. The spray of talent, the spray of ideas. One thing unlike another, one voice unlike the next. Ambiguities, contradictions, whispers, hints. And this is what you want to destroy.”

He found he was angry, unexpectedly.

“And when the novelist loses his talent, he dies democratically, there it is for everyone to see, wide open to the world, the shitpile of hopeless prose.”

He shook out a match and held it.

“Do you know why I believe in the novel? It's a democratic shout. Anybody can write a great novel, one great novel, almost any amateur off the street. I believe this, George. Some nameless drudge, some desperado with barely a nurtured dream can sit down and find his voice and luck out and do it. Something so angelic it makes your jaw hang open. The spray of talent, the spray of ideas. One thing unlike another, one voice unlike the next. Ambiguities, contradictions, whispers, hints. And this is what you want to destroy.”

He found he was angry, unexpectedly.

“And when the novelist loses his talent, he dies democratically, there it is for everyone to see, wide open to the world, the shitpile of hopeless prose.”

Don DeLillo, Mao II (A)

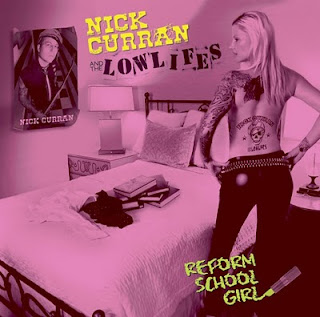

Reform School Girl by Nick Curran & The Lowlifes

When Link Wray died in 2005 the papers ran the usual stories, but the one that frequently took center stage described how Wray’s signature tune, “Rumble,” inevitably started fights on the dance floor during concerts. George Pelecanos recreated the scene early in Hard Revolution (A); after reading that, I was keen to discover the song that could summon such a tidal wave of testosterone. One quick YouTube video later, I had to scratch my head. This used to get the fellas scrapping?

Today’s noise is tomorrow’s hootenanny, as DEVO used to say. I thought nothing more of my reaction until last week, when I saw Jimmy Page trying to explain precisely just how Wray’s “Rumble” completely reshaped the foundation of rock ‘n’ roll. Page lowers the stylus onto the groove, steps back as the song plays, then points out when different shifts in distortion and reverb pull the song taut like a bowstring. For a few short seconds I could hear a little of the drama and menace that Page, and others, still hear in that song.

After American Graffiti and Happy Days and countless shake & burger stands it is remarkable to me that rockabilly hasn’t yet been reduced to tepid soundtrack fodder with all the drama of Dick Clark’s hairpiece. But as Reform School Girl by Nick Curran and The Lowlifes amply demonstrates, rockabilly still has an undeniably primal energy to it that prevents it from becoming a mainstay at Disney’s Main Street USA. As with the Stray Cats and The Blasters (note the presence of Dave Alvin in “Flying Blind”), Curran uncovers the bloody steak at the heart of rockabilly and tears off bite-sized strips for some feral audience consumption. It’s all cheap thrills and low-rent spills, and it’s still very noisy. And while that might not yet compel me to scrounge up the old motorcycle jacket, it will more than suffice to keep me humming through this spring’s wash ‘n’ wax of the family wheels. A, e.

Correction: The Zeppelin member in question was guitarist Jimmy Page, not vocalist Robert Plant, as I originally wrote.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)