That little record set something of a studio precedent for her. The sound quality was crummy - if 18-wheelers roaring through the middle of a song isn't bad enough, the tape is recorded at a speed that shoves it all up a tone or two into the stratosphere. There was no denying this kid had the goods. The trouble was, this production only kinda-sorta delivered them.

And so it was with the next few discs. Her talent was frequently a hinderance as well: she'd absorbed way too many musical genres to stick with a single one for a whole 40 minutes, and her early albums would jump from sound to sound without much (or any) transition between. Of the early discs, the one I still like best is Captain Swing. It also has a nifty anarchist aesthetic that appealed to me at the time. The fall she came through Toronto, downtown telephone poles and construction boardwalks were papered over with CS posters, one of which I peeled and stuck to the wall of my basement hovel, the better to enjoy Shocked's sassy wink.

And so it was with the next few discs. Her talent was frequently a hinderance as well: she'd absorbed way too many musical genres to stick with a single one for a whole 40 minutes, and her early albums would jump from sound to sound without much (or any) transition between. Of the early discs, the one I still like best is Captain Swing. It also has a nifty anarchist aesthetic that appealed to me at the time. The fall she came through Toronto, downtown telephone poles and construction boardwalks were papered over with CS posters, one of which I peeled and stuck to the wall of my basement hovel, the better to enjoy Shocked's sassy wink.The other discs are played rarely, if at all. I lost track of her where-and-what-abouts until just the other day, when I picked up a copy of Paste magazine (to see if there was anything by Phil in there). Turns out Ms. Shocked has recently divorced her alcoholic husband, and, in one of those post-divorce fits of energy, turned out not just one but three new albums in one go.

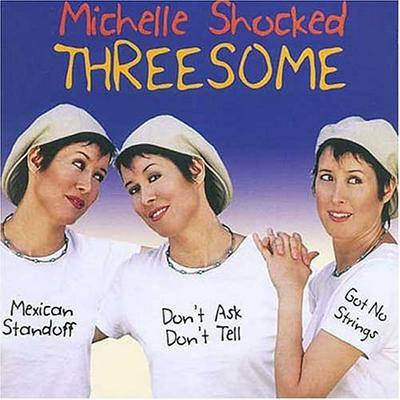

This level of productivity usually inclines me toward caution. I would likely have risked money on Don't Ask, Don't Tell - "a rock album, full of guitar and guts" - then held off on the others until a couple of spins had assured me of overall quality. This is one option; another is to go for the smashing value package (she's called it Threesome, which no doubt adds some unwanted salt to the ex's margaritas).

I've finally given all three a spin, and whaddaya know: I loves 'em all! This is exactly the studio product I've been waiting for. Mexican Standoff is a trip, Don't Ask Don't Tell is almost too upbeat and deep-down groovin' to be a divorce album, and Got No Strings...

I could see where the last item might be a stretch for some listeners, because it's a collection of lovingly rendered Disney "classics" - Wish Upon A Star, Spoonful of Sugar, Bare Necessities etc. Friends and family members who have tired from my repeated spins of Stay Awake, however, realize just how deeply this effort appeals to me. (digression: If you want "quirky" - or "uneven" - then Stay Awake is it. It served to introduce me to some terrific talent, though: NRBQ, Syd Straw, Bill Frisell and Ken Nordine were all delivered to my ears for the first time via SA.) I still recommend Threesome, because even if GNS doesn't turn your crank (and it just might) the package price is a terrific deal.

As for my wife, my oldest daughter duly noted that Ms. Shocked bears a passing (if somewhat wonky) physical resemblance to my gorgeous beloved. And if the music is any indication, I think there's a similarity of spirit as well.

(I can't seem to find the review in question, but Paste has a Michelle Shocked feature story here.)