Having seen neither movie (yet), I'll go out on a limb and suggest that as film directors, Miller and Mel have quite a bit in common, beginning with a deleterious obsession with things Catholic. But where Mel is the ardent convert, an ultra-conservative late to the fold, wielding his aesthetic like a truncheon to brow-beat viewers into the Kingdom, Miller is the raving heretic, throwing open the windows of the sanitarium and coughing in the patients' faces — brow-beating viewers in the opposite direction. With precious few exceptions, Miller's comics depict Catholic priests as shrunken, dissipated connivers, and Catholic nuns as gargantuan, hate-driven viragos capable of inflicting terrible physical humiliation (somewhere in FM's childhood, the boy must have run afoul of Miss Clavel). In nearly all of Miller's work, but especially in the Sin City books, the heretic heroes pummel, blast and dismember a barrage of holy fathers and sisters — behavior seemingly made acceptable because his priests and nuns are presented as willing co-conspirators in an enormous, corrupt regime.

Catholic authority is but one of Miller's big obsessions: others include pneumatically enhanced women with cold, cold hearts, cynically manipulative conservatives, bleeding-heart liberals, a docile and easily-duped public, malicious flying imps (often in the form of automatons), drapey trench-coats and Chuck Taylor sneakers. Miller has become that uniquely American phenomenon: he turns a profit with his public self-indulgence. His worst material is like bad heavy metal, with its tedious excesses and a head-slapping lack of self-consciousness. Conversely, his best material is like good heavy metal: it knocks you on your ass.

Catholic authority is but one of Miller's big obsessions: others include pneumatically enhanced women with cold, cold hearts, cynically manipulative conservatives, bleeding-heart liberals, a docile and easily-duped public, malicious flying imps (often in the form of automatons), drapey trench-coats and Chuck Taylor sneakers. Miller has become that uniquely American phenomenon: he turns a profit with his public self-indulgence. His worst material is like bad heavy metal, with its tedious excesses and a head-slapping lack of self-consciousness. Conversely, his best material is like good heavy metal: it knocks you on your ass.Some 20 years ago, when Miller still had an editor to answer to, he delivered the work he will be best known for: Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. Dark Knight is tightly scripted, meticulously penciled and inked, has worthy literary pretensions, and is single-handedly responsible for the current deluge of comic books on the big screen. Corruption at the highest level, moral dis-ease, the tension between anarchy and fascist totalitarianism and the desperate heave to transcend all these mortal conditions are played out with a giddy ferocity. In tone and physicality, Batman resembles Clint Eastwood's avenging angel of death, William Munny, during Unforgiven's final act.

Until the final act of Dark Knight, however, Batman more closely resembles Eastwood's The Man With No Name during his feebler hours. Batman was a bit too eager to come out of retirement, it seems. He takes a physical beating that would kill a dozen men; toward the end of the saga's early chapters, he limps about with mashed lips, missing teeth, while clutching broken ribs or an abdominal wound in his sagging costume. The man has lessons to learn before the demi-urge within can tower over the bad guys (including a gormless Superman), and the chief lesson seems to be: if the world is unimaginably corrupt, your methods of subversion have to be unimaginably extreme.

Until the final act of Dark Knight, however, Batman more closely resembles Eastwood's The Man With No Name during his feebler hours. Batman was a bit too eager to come out of retirement, it seems. He takes a physical beating that would kill a dozen men; toward the end of the saga's early chapters, he limps about with mashed lips, missing teeth, while clutching broken ribs or an abdominal wound in his sagging costume. The man has lessons to learn before the demi-urge within can tower over the bad guys (including a gormless Superman), and the chief lesson seems to be: if the world is unimaginably corrupt, your methods of subversion have to be unimaginably extreme.The Dark Knight Returns was an incredible success, and vaulted Miller into rock star status. I dabbled in comics before Frank Miller; once I recognized him, I turned the corner and became a collector. I dug the way his figures swept out into open space — often the white space between panels — with an ethereal grace, or the way they'd bunch up like a clenched fist, ready to explode. His heroes were never merely challenged or tried: they were fed into the crucible, feet first. Torment, humiliation, agony, resurrection and violent triumph — the movies weren't delivering this stuff, not as deliciously as Miller was.

(Digression: Miller's kinetic aesthetic has proven extremely difficult to translate cinematically, because his movement either defies or exaggerates gravity. He borrows heavily from the Shangri-La films, but uses drape-like clothing to add to the drama of the printed page in a way that, until the advent of digital film-making, was impossible to capture. Think of the trench-coated Neo, dodging bullets in the Matrix. Or think of Mr. Incredible purposely leaping off a cliff and falling for half-a-mile before catching a palm tree that flings him gymnastically to the next level. Prior to this we had Rambo, impaling himself on a towering evergreen.)

As good as The Dark Knight Returns was, it was only the launching pad for his best, most controversial project — Elektra: Assassin. Miller took the unusual step of teaming up with artist Bill Sienkiewicz, a man whose conceptual approach was hallucinatory, borderless and garishly, oppressively colored. Collaborating board by board with Sienkiewicz, Miller cooked up a story that played like a Road Runner cartoon envisioned by Hieronymous Bosch. As with Road Runner, Elektra is the ostensible hero of the series, but she is something of a cipher, and the villain chasing her becomes the story's true moral center — which poses a serious problem. Garrett is a government operative, a certified psychopath employed only because he's been physically tinkered with: several limbs are artificial, giving him powers he is incapable of dealing with responsibly.

He chases after Elektra, brandishing bombs and guns and lethal Rube Goldberg devices, all of which boomerang on him. With every foiled plot, he loses more of his genuine self, until the only thing that isn't artificial is a portion of his head. With this compromised instrument, he is able to reach two crucial realizations: he has fallen hopelessly in love with his nemesis, a woman whose cruel streak exceeds his own by a grotesque margin; and she herself is chasing after bigger fish — in this case the Antichrist, a charismatic demon-possessed Democrat set to unleash nuclear annihilation once he gets into office.

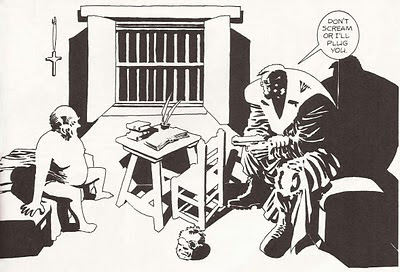

If my summary sounds comic, the true effect of the book has to be experienced to be believed. At the time (Reagan's second term in office), it did a good job of rattling my cage, and a bunch of other people's, too. It fueled several loud calls for censorship, which Miller's publishers promptly used in their promotional materials. I suppose you could say Miller excelled at the "how" of what his material was about. Guess who's narrating here (Hint: it's not the guy holding the head):

And what was it about? Same old same old. The world is a scary place; the political and religious powers that be are corrupt beyond imagining and wildly out of control, tainting the well-intentioned when they aren't abusing them outright; and only extreme subversion can possibly curb their grim direction — momentarily. Elektra: Assassin is a tour de force that should not be read at too tender an age, or before going to sleep.

And what was it about? Same old same old. The world is a scary place; the political and religious powers that be are corrupt beyond imagining and wildly out of control, tainting the well-intentioned when they aren't abusing them outright; and only extreme subversion can possibly curb their grim direction — momentarily. Elektra: Assassin is a tour de force that should not be read at too tender an age, or before going to sleep.Following Elektra: Assassin, Frank Miller's Sin City books seem almost like an afterthought. By now his characters go through the paces. Everything has the Frank Miller look, which never gets boring, but it decorates the trademark Frank Miller plot we've come to expect. It amounts to maladjusted behavior in a shiny package, which at least has the courage of its thin convictions. Miller knows you didn't buy Sin City, or pay admission to see a movie like The Patriot, because you want to see a man find his soul: you spent the money to see some fucked-up shit, and he delivers. If it doesn't scare you the way Elektra: Assassin did, it's because Miller no longer needs to put everything on the line to get your money. Sin City is the equivalent of the last 12 albums by the Rolling Stones, or the last seven by AC/DC: the eleven herbs and spices are all there, but the nutritional foundation has been processed into near non-existence. It's junk-food for the soul — a little of it shouldn't hurt you, but you're arguably better off without it.

If that last declaration places me amongst the blue-hairs, so be it. Hey, I like junk-food, too, but I'm at the age where I have to limit my intake. And let's be honest: that age is any age. Youthful readers who wish to quibble should try this little exercise: hold your own Robert Rodriguez film festival, starting with El Mariachi, Desperado, the three Spy Kids movies, and concluding with Sin City. When it's over, step outside and take a long, deep breath. Look around you, or talk to your neighbor for a few minutes. Then return to your darkened TV set, and see if you don't feel — just a little — like Morgan Spurlock after eating a month's worth of McDonald's.

5 comments:

That last paragraph was genius! You're so good, it pains me.

But why haven't you seen "Passion of the Christ" yet? Yours is one of the few opinions I'd be interested in hearing on this one :D

The Passion, yes ... I'm not sure why I'm so terribly disinclined to watch it. I naturally bristle at any religious proscription, which helps, but my aversion to this movie runs deeper than that. It is a rare non-canonical portrait of Jesus that doesn't irk me, if not set me seething. What I usually encounter is someone else's personality, and not a very compelling one at that. In contrast, the Jesus I encounter in the Gospel narratives becomes more enticing, more maddening, and more frightening with every reading. I have a difficult enough time with that Jesus, I guess.

Not sure why you're so terribly disinclined to watch it? Wouldn't over two hours of Catholic torture-porn make you feel closer to our Lord?

I can see why you're irked by cinematic portrayals of Christ, though -- my favourite is the fifties' "King of Kings" with its cheerfully-offensive casting of Jeffrey Hunter as 'the pretty Jesus'! It amuses me to no end. (I still maintain, however, that Willem Dafoe did a great job in the Scorsese movie.)

Your comments on the textual Jesus intrigue me, since I find the person in the Bible a far more wise, compassionate and (gasp!) liberal figure than the creepy Ted Nugent figure I keep seeing on protest signs at women's clinics. There's just too many Jesuses (Jesei?)

"Willem Dafoe" - I'd modify "great" to "watchable". Opening The Sermon On The Mount with, "Um ... I've never done this before" was even more risible than "Blessed are the Cheese-makers"! The latter comes from my favorite Jesus-pics, Monty Pyton's The Life Of Brian - but then, it's not really about Jesus, is it?

As for the liberal Jesus in the Gospels, it seems to me he was liberal with everyone except the people who followed him. With the disciples, he snipes, snarks, expresses great impatience. Passionate Peter - the only disciple to walk on water, an obvious crowd-pleaser and the "Rock" upon which the Church is built - seems to try him especially: "Get thee behind me, Satan!" Good grief! It's enough to make you think twice (at the least) about claiming to be His follower!

Thanks for writing this. I just blogged a piece about Frank Miller's incredible impact on my childhood followed by his descent into repitition and irrelevance. Realising just how influential his work was to me for years I was feeling bad about dismissing all his post '80s work. Then I come across your piece and realize that I am not the only one who isn't thrilled by the Sin City stuff. Elektra: Assassin, however, is still amazing. Thanks for writing.

IK

Post a Comment