I've been re-shuffling my links, introducing a new category titled (at present) "Lecterns & Pulpits." I got to thinking I should corral my more overtly religious and political friends and links into an appropriately designated section of the farmyard. I'm not altogether sure what's behind this impulse, but I suspect my overriding desire to avoid reader offence or annoyance is a strong motivation.

Curious how frequently it is the conceptual "stuff" that gets a reader's blood up. Or raises their

hackles. Or any other colorful metaphor that best illustrates an individual's impulse toward defensiveness — and I certainly include myself, here. Any writer seeking a quick response from readers should either a) come out loud and proud of his particular world-view and b) point out the inconsistencies of someone else's, particularly if the Other is in the perceived social majority.

These skirmishes can't be completely avoided, and perhaps my efforts to do so are worse than self-defeating. Reading

Searchie's espousal of

The 51% Solution I can't help but wonder if I'm not drifting around at 49%, or some lesser grade of conviction (

W.B. Yeats save us all!). And when I consider her friend's attempt at book promotion, I wonder if depression isn't just as surely a religious issue as it is physical, emotional, experiential, existential, etc. But don't ask me to define my terms, because I'll get dodgy on you. The clearest I can be is to say, I haven't yet read my (pastor) father's

recommended reading, either.

In fact, I'm slow to pick up

any recommended religious reading. More often than not, what I do pick up is something I've seen on a blogger's sidebar. If it looks interesting or pertinent to my situation, I'll see if I can't track down a copy. If I'm put-off by what I've read, the only recipient of my disappointment is the author.

A friend of mine once saw a book on my shelf and asked if she could borrow it. I hesitated because the book had been given to me by someone of a more conservative stripe than I, which meant its contents were

considerably more conservative than my friend was. I finally figured,

She's a big girl and she doesn't have to like a book she pulls off my shelf, and I don't have to hold that against her. But my impression was correct: the book really bugged her.

We had a stimulating and entirely pleasant conversation after that, but it concluded with her recommending I read

The Pagan Christ. Suddenly we were again in problematic territory. As with the book she had borrowed, I was now figuratively in possession of a point of view someone else held dear, but which I had limited use for. That's the problem with recommended religious reading: the material promoted rarely settles for giving the intended reader a clear idea of where the book-giver is coming from — it often suggests, or states outright, that what the reader currently holds to is a crock of shit.

I may yet use this blog to flesh out some of my religious ideological identity. I'm not particularly logical in my thinking, and when I'm systematic it's in a base and intuitive fashion. I am who I am via a series of episodes and encounters. Occasionally music and books have brought significant comfort or encouragement. In aid of doing a little self-corralling, I will confess: my current way of thinking and to some degree behaving is a farm-hand philosopher's response to

Pascal's Wager, followed by an

Aristotelian shrug;

Northrop Frye's exploration of myth, narrative, culture and Christianity (

here and

here) speaks to my heart with more eloquence and greater acuity than does

Tom Harpur's (which, his own frequent assertions to the contrary, were neither shocking nor helpful); and with one sole exception, the significant religious leaders in my life have all been women.

In the (so far as I'm concerned) non-hackle-raising department:

Prairie Mary considers dinner with some

interesting company. I'm happy to be reminded of

Searchie's fondness for

What I Loved by Siri Hustvedt (which I commented on

here). I believe Searchie just about embodies Ms. Hustvedt's ideal reader, and that's no small compliment. And as for

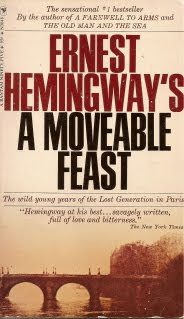

this Miles, I shall get to him. For now,

this is the Miles I'm studying.