Religion complicated this relationship (as it does them all): my father was the pastor of the church, and our family was expected to be at the opening of church doors, just prior to the start of the service. This meant turning off the television 10 minutes before the conclusion of the hour. To this day, Old Yeller remains clutched in my memory as a rabid, angry dog who turns on his masters.

Nevertheless, Disneyland managed to serve not just the Magic Kingdom, but the Kingdom of God as well. After a particularly grueling Q&A I had with my father, hashing through the details of the Hereafter, and expressing my doubts about its appeal, he finally proclaimed, "Well, think of it like you do Disneyland — only 100 times better!" He seemed to slump a bit after saying this, as if such a base appeal to sensory pleasure might compromise my burgeoning piety, but his strategy was hardly unprecedented: it's a tack our Savior took many a time himself.

The Disneyland standard remained untarnished by reality, until puberty took over and ratcheted my base sensory expectations in an entirely different direction. Our family finally made the California trip when I was old enough to drive the car, and if seeing the park for the first time wasn't exactly a let-down, it was only because my expectations of it — and life — had become a bit more sophisticated.

Still, in 1982 Disneyland was not only underwhelming, but even a wee bit shabby. The most recent attraction in the park was the Haunted Mansion, and it was over a decade old. Everything showed signs of age, but the worst of the lot was Tomorrowland. The submarine ride was being dismantled, Mission To Mars was creaky with age, the highlight of Adventure Through Inner Space was a giant eyeball looking down at you, Autopia was a bunch of go-karts fouling up the air with their two-stroke engines. The only worthwhile ride was Space Mountain, and even it paled in contrast to a real roller coaster. Worst of all, my newly discovered sense of irony was worthless in this run-down corner. In the Reagan years, space was being flagged for militarization, not colonization, so even when I tried to enjoy the Kennedy-era kitsch factor, my efforts concluded with depression.

Flash forward 22 years to the present, and the future ain't what it used to be. My parents generously treated our family, taking the two grandchildren to the tea-cups, where they spent most of the day, while I took my wife by the hand and strolled through Tomorrowland — where I would have spent most of the day, had she indulged this dangerous impulse of mine. The Imagineers have cleaned it up, and tweaked the aesthetic in an interesting, if no less depressing, direction. Like so many other commercial commodities, the future can no longer be relied upon to supply an optimistic aesthetic, so the Imagineers have dipped even further into the past. Tomorrowland is now shaped as much by the aesthetic of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon as it is the Kennedy era. Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon — movie serials that my grandparents recalled with some amusement, but never wistfullness.

Main Street USA doesn't mean much to Gen X, but Tomorrowland sure does — it's the ultimate rec room, where we spent our childhood and held on to our adolescence. I loved it, but there is an irony here, when you consider the possibilities this realization generates. Who knows? Perhaps Frontierland, with its Davy Crockett trappings, is the next generation's Tomorrowland — an opportunity for the Prajer grandkiddies to mainline a nostalgia formed in utero by the cowboy shows their Gen X parents deemed too goofy to watch.

|

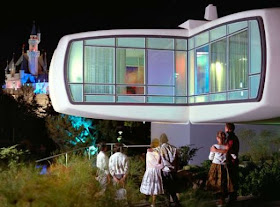

| Oh, Blue Fairy: please bring back the Monsanto House Of The Future! |

No comments:

Post a Comment