Yesterday evening my older daughter was fidgeting at the dinner table. "What's up?" asked my wife.

"No! I don't want to talk about it!" was our daughter's uncharacteristic response.

We asked a few friendly questions, and she quickly revealed that while she was visiting a friend they'd spent some time exploring one of those "Oh, The Changes You're About To Go Through" books. I was grateful for my wife's presence; I've handled some of those questions in the past, but the girls take greater comfort from her answers than they do mine. And so they should.

My daughter was duly freaked out by the spectre of the menstrual cycle and the various apparatuses associated with its accommodation. She was less than thrilled to be facing this change from little girl to young woman. And after she and her friend had looked at the book, she said, "We wrapped it in a blanket and threw it in a corner of the room!"

I can certainly sympathize. Hell, I can empathize: I'm reluctant to see her change, too. I remember holding her just a few days after her birth, staring at this new creature and thinking, "She's already changed! This is all happening too fast!!"

This is all happening too fast. Even the changes occurring in my own body are taking place at a faster rate than I care to acknowledge. And where can we turn for a little perspective? People my age don't get reading material that's as revolutionary as what our children are reading; we get pre-digested bulletins. You're body is changing, but you can slow it down a bit if you go for a daily walk and maintain a high-fibre diet, buttressed by fish-oil and green tea. Hardly the sort of clarion call my daughter is hearing: Get Ready For Puberty!

I can remember reading those books at roughly her age. I felt some of that same mixture of fear and anticipation, but mostly I remained confused. Forewarned is forearmed, but information is a far cry from actual experience and the latter eventually brings some degree of ability if not actual comfort.

But when it comes to adulthood, can experience alone generate this familiarity and comfort? I'm not so sure. This year, aside from receiving the usual updates about the Disappearing Generation (now almost gone) I experienced the loss of two friends. I've watched my daughters grow silent as they grow up, cultivating their inner life and acquiring the necessary secrets. I want to believe I'm not growing strange myself, but of course I am changing, too. As I've hobbled around this house and yard, occasionally putting a hand to my bowing gut or disappearing chin, I've been forced to admit that acquiring a sense of humour about this particular phase in life is proving to be more elusive than I'd anticipated. You'd think spending my birthday ingesting antibiotics while sick in bed might help me get some perspective. Indeed I'd say I received, to quote David St. Hubbins, "Too much!! Too much @*%#ing perspective!"

So what's my next Book of Secrets — the book I don't just push away, but actually try to hide from myself? Does it even exist, or is it up to me to write it?

Do I even want to write such a thing? Or is that even a choice that any of us faces? Our lives are bracketed by circumstances and events. We write what we can in the spaces between. We write with fear and laughter ... or we don't write at all.

Is that it? Or is there some element lurking here that I'm deliberately avoiding because I've already wrapped it up in a blanket and stowed it away?

“he”/“him” A Canadian Prairie Mennonite from the '70s & '80s, a Preacher’s Kid, slowly recovering from a hemorrhagic stroke. I am not — yet — in a 12-Step Program.

Pages

▼

Tuesday, July 31, 2007

Friday, July 27, 2007

"Ah, the bucolic summers of small-town Canada!"

It's been a lovely summer by Ontario standards — warm and breezy, rather than the humid and hot suffocation we're used to. Still, so long as heating and food are not an issue, I generally prefer winter to summer because winter is quiet. Small towns don't have quiet summers. Their youths are too busy walking up and down the streets deep into the night, getting angrier and angrier because "there's nothing to do." Tempers get especially tetchy if the kids have indulged in the latest chemical concoction. Now that marijuana is being laced with crank, the only way a kid's going to get mellow is through clean living. Fie on that! Let's do something nasty! Break a window, steal something! Start a fight! Start a fire!!

I'll never forget our meeting with the lawyer when we bought the house here. He had this beatific smile on his face as we signed the papers. "So, small town living, eh?" said he. "The great thing about small towns is they have so much less crime."

He went on to expound the hoary theory that because everyone knew everyone, the parents of would-be offenders were shamed into tightening the leash on their kids. Clearly this was not a criminal lawyer. We were looking forward to the move from city to small town, but harbored no illusions about the crime rate. My in-laws were already living here, and gave us updates on who'd been arrested for what. Besides, I'd spent half my childhood in a small town, half in the city, and could attest that the number of times I'd been offered "a thumping" (or worse) by townies greatly exceeded any such threats I'd received from cityfolk — and I'd been an urban cyclist.

In the eight years we've lived here, I've only called the police twice (last night being the second time, which is what gets me musing). Mind you, there again I'm faced with a disparity: my previous decade in the city only required one such summons, and that was over a case of double-parking. Out here I made both calls out of concern for my family's safety.

Last night's episode didn't amount to much. Some kids appeared to be interested in our shed, and a pickup truck was parked nearby. This was at 2:00 in the morning, so I made the call. Had it been daylight, I would have walked over and introduced myself but given the hour I figured the police were better equipped for that sort of thing. Three cruisers and a lot of high-beam searchlighting later, the kids were gone while the pickup truck remained. The owner of the truck couldn't be found, but this morning he got in and drove off as if nothing had happened.

In the end, I guess nothing did. All in all a quiet night, really. Just not as quiet as it gets in winter.

I'll never forget our meeting with the lawyer when we bought the house here. He had this beatific smile on his face as we signed the papers. "So, small town living, eh?" said he. "The great thing about small towns is they have so much less crime."

He went on to expound the hoary theory that because everyone knew everyone, the parents of would-be offenders were shamed into tightening the leash on their kids. Clearly this was not a criminal lawyer. We were looking forward to the move from city to small town, but harbored no illusions about the crime rate. My in-laws were already living here, and gave us updates on who'd been arrested for what. Besides, I'd spent half my childhood in a small town, half in the city, and could attest that the number of times I'd been offered "a thumping" (or worse) by townies greatly exceeded any such threats I'd received from cityfolk — and I'd been an urban cyclist.

In the eight years we've lived here, I've only called the police twice (last night being the second time, which is what gets me musing). Mind you, there again I'm faced with a disparity: my previous decade in the city only required one such summons, and that was over a case of double-parking. Out here I made both calls out of concern for my family's safety.

Last night's episode didn't amount to much. Some kids appeared to be interested in our shed, and a pickup truck was parked nearby. This was at 2:00 in the morning, so I made the call. Had it been daylight, I would have walked over and introduced myself but given the hour I figured the police were better equipped for that sort of thing. Three cruisers and a lot of high-beam searchlighting later, the kids were gone while the pickup truck remained. The owner of the truck couldn't be found, but this morning he got in and drove off as if nothing had happened.

In the end, I guess nothing did. All in all a quiet night, really. Just not as quiet as it gets in winter.

Wednesday, July 25, 2007

Defending Culture vs. Defending Your Job

I thought I'd riff off of some other bloggers, chiefly Prairie Mary (here and here) and Michael Blowhard (here). It's curious, I think, to note where the dividing line has been drawn in the supposed conflict between arts-talk on blogs vs. arts-talk in newspapers and magazines. Lately the chattering classes have devoted their verbiage to resuscitating the dying "Book Reviews" of various large-distribution newspapers. The tactic of choice, it seems, is to denigrate bloggers as merely "opinionated" while upholding critics as "learned" (would-be generals in this "fight" include Richard Schickel and Lindsay Waters).

My question is, who, exactly, are these arguments directed toward? Perhaps Schickel wrote in the hope he might spur the declining readership of the LA Times to champion the restoration of its Book Review. If that was indeed the case, I'd suggest his supercilious tone was a grievous misstep: anyone who could be bothered to read his jeremiad was likely a) a literate blogger and/or b) an employee of the publishing industry. Schickel and his fellow culture vultures would do well to attend Sunday morning church or Shabbat synagogue. In our circles it's common knowledge that a pastor/rabbi can only do so much finger-wagging at the congregation before attendance — and the offering envelope — take a hit.

It's also disingenuous to attack people who consider, promote or flame particular aspects of "arts culture" in their spare time for free (especially after praising Orwell for writing on the cheap). Culture is not what's being defended, here. Culture is simply humanity-dependent, and ebbs and flows in whatever direction humanity is pointed. Take what comfort you can from that observation and move on.

I'm guessing Schickel's target audience was his boss. If that's the case, his strategy was, on the face of it, quite brilliant. By now the number of people linking to his piece probably exceeds the number of people who subscribe to the Times. "Hey Boss, dig this: two months later and people are still linking to me! Now, uhm, could we talk about my contract?" It's a clever gimmick, but its novelty dooms it (and possibly RS) to the status of one-hit wonder. How does public consumption of this piece rate next to, say, any of his glowing reviews of Clint Eastwood?

Critics are right to be concerned — whenever my job is on the line I do some hustling, too. But if, as is commonly claimed, the web is killing the newspaper (and publishing, and music, etc.) is it really such a good idea to berate its most active participants?

My question is, who, exactly, are these arguments directed toward? Perhaps Schickel wrote in the hope he might spur the declining readership of the LA Times to champion the restoration of its Book Review. If that was indeed the case, I'd suggest his supercilious tone was a grievous misstep: anyone who could be bothered to read his jeremiad was likely a) a literate blogger and/or b) an employee of the publishing industry. Schickel and his fellow culture vultures would do well to attend Sunday morning church or Shabbat synagogue. In our circles it's common knowledge that a pastor/rabbi can only do so much finger-wagging at the congregation before attendance — and the offering envelope — take a hit.

It's also disingenuous to attack people who consider, promote or flame particular aspects of "arts culture" in their spare time for free (especially after praising Orwell for writing on the cheap). Culture is not what's being defended, here. Culture is simply humanity-dependent, and ebbs and flows in whatever direction humanity is pointed. Take what comfort you can from that observation and move on.

I'm guessing Schickel's target audience was his boss. If that's the case, his strategy was, on the face of it, quite brilliant. By now the number of people linking to his piece probably exceeds the number of people who subscribe to the Times. "Hey Boss, dig this: two months later and people are still linking to me! Now, uhm, could we talk about my contract?" It's a clever gimmick, but its novelty dooms it (and possibly RS) to the status of one-hit wonder. How does public consumption of this piece rate next to, say, any of his glowing reviews of Clint Eastwood?

Critics are right to be concerned — whenever my job is on the line I do some hustling, too. But if, as is commonly claimed, the web is killing the newspaper (and publishing, and music, etc.) is it really such a good idea to berate its most active participants?

Thursday, July 19, 2007

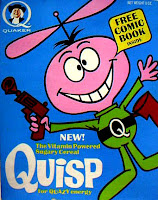

"Today's posting brought to you by Quisp and Quake!"

It's Cowtown Pattie's fault: she located this TV ad from her youth. Now here is one from mine: New & Improved Quake Cereal, with a guest appearance by Quisp. I would have been about four years old when I saw this.

It's Cowtown Pattie's fault: she located this TV ad from her youth. Now here is one from mine: New & Improved Quake Cereal, with a guest appearance by Quisp. I would have been about four years old when I saw this.I'd be curious to find out how people get footage of stuff like this. What events does a collector of Jay Ward animation need to attend to complete his or her collection of cereal commercials?

Here is the Wikipedia entry for Quisp. I, like others of my generation, preferred it to Quake. Obviously there was no difference in taste or texture — both were a softer concoction of Cap'n Crunch, as the entry points out — but staring at this cheerful googly-eyed propeller-head was a happier prospect than staring at a) a skull-thumping miner or b) a barrel-chested galoot. Ward must have known this.

And since I'm already YouTubing, here is a perfect example of how the White Stripes get under my skin in the most unpleasant way (Here is the rest of the story. Both via Boing Boing. ).

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

Getting to Miles, Take 2

I've been re-shuffling my links, introducing a new category titled (at present) "Lecterns & Pulpits." I got to thinking I should corral my more overtly religious and political friends and links into an appropriately designated section of the farmyard. I'm not altogether sure what's behind this impulse, but I suspect my overriding desire to avoid reader offence or annoyance is a strong motivation.

Curious how frequently it is the conceptual "stuff" that gets a reader's blood up. Or raises their hackles. Or any other colorful metaphor that best illustrates an individual's impulse toward defensiveness — and I certainly include myself, here. Any writer seeking a quick response from readers should either a) come out loud and proud of his particular world-view and b) point out the inconsistencies of someone else's, particularly if the Other is in the perceived social majority.

These skirmishes can't be completely avoided, and perhaps my efforts to do so are worse than self-defeating. Reading Searchie's espousal of The 51% Solution I can't help but wonder if I'm not drifting around at 49%, or some lesser grade of conviction (W.B. Yeats save us all!). And when I consider her friend's attempt at book promotion, I wonder if depression isn't just as surely a religious issue as it is physical, emotional, experiential, existential, etc. But don't ask me to define my terms, because I'll get dodgy on you. The clearest I can be is to say, I haven't yet read my (pastor) father's recommended reading, either.

In fact, I'm slow to pick up any recommended religious reading. More often than not, what I do pick up is something I've seen on a blogger's sidebar. If it looks interesting or pertinent to my situation, I'll see if I can't track down a copy. If I'm put-off by what I've read, the only recipient of my disappointment is the author.

A friend of mine once saw a book on my shelf and asked if she could borrow it. I hesitated because the book had been given to me by someone of a more conservative stripe than I, which meant its contents were considerably more conservative than my friend was. I finally figured, She's a big girl and she doesn't have to like a book she pulls off my shelf, and I don't have to hold that against her. But my impression was correct: the book really bugged her.

We had a stimulating and entirely pleasant conversation after that, but it concluded with her recommending I read The Pagan Christ. Suddenly we were again in problematic territory. As with the book she had borrowed, I was now figuratively in possession of a point of view someone else held dear, but which I had limited use for. That's the problem with recommended religious reading: the material promoted rarely settles for giving the intended reader a clear idea of where the book-giver is coming from — it often suggests, or states outright, that what the reader currently holds to is a crock of shit.

I may yet use this blog to flesh out some of my religious ideological identity. I'm not particularly logical in my thinking, and when I'm systematic it's in a base and intuitive fashion. I am who I am via a series of episodes and encounters. Occasionally music and books have brought significant comfort or encouragement. In aid of doing a little self-corralling, I will confess: my current way of thinking and to some degree behaving is a farm-hand philosopher's response to Pascal's Wager, followed by an Aristotelian shrug; Northrop Frye's exploration of myth, narrative, culture and Christianity (here and here) speaks to my heart with more eloquence and greater acuity than does Tom Harpur's (which, his own frequent assertions to the contrary, were neither shocking nor helpful); and with one sole exception, the significant religious leaders in my life have all been women.

In the (so far as I'm concerned) non-hackle-raising department: Prairie Mary considers dinner with some interesting company. I'm happy to be reminded of Searchie's fondness for What I Loved by Siri Hustvedt (which I commented on here). I believe Searchie just about embodies Ms. Hustvedt's ideal reader, and that's no small compliment. And as for this Miles, I shall get to him. For now, this is the Miles I'm studying.

Curious how frequently it is the conceptual "stuff" that gets a reader's blood up. Or raises their hackles. Or any other colorful metaphor that best illustrates an individual's impulse toward defensiveness — and I certainly include myself, here. Any writer seeking a quick response from readers should either a) come out loud and proud of his particular world-view and b) point out the inconsistencies of someone else's, particularly if the Other is in the perceived social majority.

These skirmishes can't be completely avoided, and perhaps my efforts to do so are worse than self-defeating. Reading Searchie's espousal of The 51% Solution I can't help but wonder if I'm not drifting around at 49%, or some lesser grade of conviction (W.B. Yeats save us all!). And when I consider her friend's attempt at book promotion, I wonder if depression isn't just as surely a religious issue as it is physical, emotional, experiential, existential, etc. But don't ask me to define my terms, because I'll get dodgy on you. The clearest I can be is to say, I haven't yet read my (pastor) father's recommended reading, either.

In fact, I'm slow to pick up any recommended religious reading. More often than not, what I do pick up is something I've seen on a blogger's sidebar. If it looks interesting or pertinent to my situation, I'll see if I can't track down a copy. If I'm put-off by what I've read, the only recipient of my disappointment is the author.

A friend of mine once saw a book on my shelf and asked if she could borrow it. I hesitated because the book had been given to me by someone of a more conservative stripe than I, which meant its contents were considerably more conservative than my friend was. I finally figured, She's a big girl and she doesn't have to like a book she pulls off my shelf, and I don't have to hold that against her. But my impression was correct: the book really bugged her.

We had a stimulating and entirely pleasant conversation after that, but it concluded with her recommending I read The Pagan Christ. Suddenly we were again in problematic territory. As with the book she had borrowed, I was now figuratively in possession of a point of view someone else held dear, but which I had limited use for. That's the problem with recommended religious reading: the material promoted rarely settles for giving the intended reader a clear idea of where the book-giver is coming from — it often suggests, or states outright, that what the reader currently holds to is a crock of shit.

I may yet use this blog to flesh out some of my religious ideological identity. I'm not particularly logical in my thinking, and when I'm systematic it's in a base and intuitive fashion. I am who I am via a series of episodes and encounters. Occasionally music and books have brought significant comfort or encouragement. In aid of doing a little self-corralling, I will confess: my current way of thinking and to some degree behaving is a farm-hand philosopher's response to Pascal's Wager, followed by an Aristotelian shrug; Northrop Frye's exploration of myth, narrative, culture and Christianity (here and here) speaks to my heart with more eloquence and greater acuity than does Tom Harpur's (which, his own frequent assertions to the contrary, were neither shocking nor helpful); and with one sole exception, the significant religious leaders in my life have all been women.

In the (so far as I'm concerned) non-hackle-raising department: Prairie Mary considers dinner with some interesting company. I'm happy to be reminded of Searchie's fondness for What I Loved by Siri Hustvedt (which I commented on here). I believe Searchie just about embodies Ms. Hustvedt's ideal reader, and that's no small compliment. And as for this Miles, I shall get to him. For now, this is the Miles I'm studying.

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

Reading Wood via Teachout, and getting to Miles

Terry Teachout has undertaken an unusual posting theme for Tuesdays: 5 X 5, or five recommended books. When he launched the concept, I thought the task he'd set for himself was a tad lofty, even for a guy who writes and reads as much as he does. But yesterday, his second Tuesday, he listed five titles from Mark Sarvas' James Wood reading list. Yes, well ... I have a friend on the south side of the hill who reads more voraciously than I and could provide five new recommended titles for my blog every week, too.

Still, it's quite the list and my eye finally settled on the last of the five — God: A Biography, by Jack Miles. Curiously, this is a book my father recommended to me. Wood is someone I admire for his intelligent criticism, but he's also someone with whom I feel some affinity because he's a pastor's kid who seems to read and write in the hope of discovering something holy. Here Wood uses God: A Biography as a standard with which to judge some of Harold Bloom's religious musings. And here Wood gives Miles' follow-up, Christ: A Crisis In The Life Of God, his full attention.

As for my own thoughts re: Miles, I'm rather embarrassed to admit I haven't read him — yet. And on that issue, I'm sure Reverend Wood and my father could easily relate.

Still, it's quite the list and my eye finally settled on the last of the five — God: A Biography, by Jack Miles. Curiously, this is a book my father recommended to me. Wood is someone I admire for his intelligent criticism, but he's also someone with whom I feel some affinity because he's a pastor's kid who seems to read and write in the hope of discovering something holy. Here Wood uses God: A Biography as a standard with which to judge some of Harold Bloom's religious musings. And here Wood gives Miles' follow-up, Christ: A Crisis In The Life Of God, his full attention.

As for my own thoughts re: Miles, I'm rather embarrassed to admit I haven't read him — yet. And on that issue, I'm sure Reverend Wood and my father could easily relate.

Monday, July 16, 2007

What I Loved by Siri Hustvedt, Little Children by Tom Perrotta

Whenever an artist dies, the work slowly begins to replace his body, becoming a corporeal substitute for him in the world. It can't be helped, I suppose. Useful objects, like chairs and dishes, passed down from one generation to another, may briefly feel haunted by their former owners, but that quality vanishes rather quickly into their pragmaic functions. Art, useless as it is, resists incorporation into dailiness, and if it has any power at all, it seems to breathe with the life of the person who made it. Art historians don't like to speak of this, because it suggests the magical thinking attached to icons and fetishes, but I have experienced it time and time again, and I felt it in Bill's studio ... Although I knew better than most people that Bill himself and Bill's art were not identical, I understood the need to grant an aura to the work he had left behind him — a kind of spiritual halo that resists the harsh truths of burial and decay. What I Loved, Siri Hustvedt.

I'll confess I wasn't as taken with this novel as so many people seem to be. Part of my reaction is tied to a very gradual cooling I've had toward the work of Paul Auster, her husband (I still recommend Moon Palace to just about anyone). Hustvedt's own style and voice is often quite similar ("It can't be helped, I suppose" is the exactly the casual sort of toss-off that Auster's narrators pepper their stories with), and her concerns — art, identity, the public appropriation of same — align closely with some of Auster's.

For those of us who read the headlines, there is a prurience factor that can't be discounted: a great deal of the novel is devoted to parsing apart the seemingly psychotic behavior of a beloved stepson. What role does therapy or even salvation play in the artistic process?

I can't imagine Hustvedt is being anything but genuine when she brings the intensity of her focus to bear on these questions, but I also couldn't help but contrast the novel's observations with those of Little Children, by Tom Perrotta. Both novels present young children as ciphers, but where Hustvedt's progeny are articulate and frequently precious, Perrotta's kids are recognizably self-centred and manipulative — and, for all that, entirely loveable, too.

Despite the title, Perrotta's chief concern isn't children, but their parents, who seem to be having a tough time figuring out what passes for adult behavior in a physically comfortable, American middle-class environment. This is a concern that strikes a little closer to my heart than those of WIL, and Perrotta explores it with an honesty that had me giggling and squirming in equal measure. In another time and place, I would have immersed myself in Hustvedt's world, and probably emerged from it quite shaken and stirred. But at this moment, my highest recommendation goes to Perrotta. So far, Little Children has been my favourite read this year.

I'll confess I wasn't as taken with this novel as so many people seem to be. Part of my reaction is tied to a very gradual cooling I've had toward the work of Paul Auster, her husband (I still recommend Moon Palace to just about anyone). Hustvedt's own style and voice is often quite similar ("It can't be helped, I suppose" is the exactly the casual sort of toss-off that Auster's narrators pepper their stories with), and her concerns — art, identity, the public appropriation of same — align closely with some of Auster's.

For those of us who read the headlines, there is a prurience factor that can't be discounted: a great deal of the novel is devoted to parsing apart the seemingly psychotic behavior of a beloved stepson. What role does therapy or even salvation play in the artistic process?

I can't imagine Hustvedt is being anything but genuine when she brings the intensity of her focus to bear on these questions, but I also couldn't help but contrast the novel's observations with those of Little Children, by Tom Perrotta. Both novels present young children as ciphers, but where Hustvedt's progeny are articulate and frequently precious, Perrotta's kids are recognizably self-centred and manipulative — and, for all that, entirely loveable, too.

Despite the title, Perrotta's chief concern isn't children, but their parents, who seem to be having a tough time figuring out what passes for adult behavior in a physically comfortable, American middle-class environment. This is a concern that strikes a little closer to my heart than those of WIL, and Perrotta explores it with an honesty that had me giggling and squirming in equal measure. In another time and place, I would have immersed myself in Hustvedt's world, and probably emerged from it quite shaken and stirred. But at this moment, my highest recommendation goes to Perrotta. So far, Little Children has been my favourite read this year.

Friday, July 13, 2007

Today In Business

"Honest Ed" Mirvish gets buried, and Conrad Black gets convicted.

If there's a Torontonian inclined to speak poorly of Ed, I've yet to make their acquaintance. I'm sure he pissed someone off: he was a businessman and a success, which requires some steel and ruthlessness. But whatever bad karma he may have kicked into motion he more than made up for with his turkey give-aways and cheerful, deliberately low-rent star schmoozing. He insisted he was just one of the regular people, even as he blew a fortune attempting to make downtown Toronto the Canadian "Great White Way." And no-one doubted him because, well, he obviously was who he was.

And just who is shedding tears on behalf of Conrad? Hard to say, though there are Canada Post writers who will talk about what a treat it was to work for him. I don't doubt it. In his inevitably massive way Conrad Black attempted to be an "Honest Ed" on behalf of the entire nation by throwing his considerable clout into breaking the hegemony of Toronto's national newspaper. While he was at it, he took a vigorous stab at keeping Canada's oldest magazine alive, as well. Personally, I thought it was all great fun -- the country needed this hubris-driven craziness. Pierre Elliott Trudeau pulled it off, but he had to dip deep into the people's purse; if the free-market really is superior to all that, why couldn't an unfettered capitalist achieve a visibly public legacy similar in scale?

But you can only hemorrhage money on such an enterprise for so long before your interests are distracted by something flashier, like becoming a Lord. And pissing off that gnarled toad in the PMO. And writing a laudatory biography of Richard M. Nixon that sits at 1148 pages.

Black lost my sympathies somewhere down that road. It could have been that smirk on his face while he wore those funny clothes, I dunno .... But whatever he's guilty of, I'm sure it's incredibly big, because Black isn't a person who does anything on a small scale.

And yet today's headlines somehow do make him seem smaller, like the ex-husband who's finally lost his fortune and his arm-candy. If only he'd stuck to Canada, maybe we'd still love him.

Ed Mirvish, 1914-2007: a guy who knew how to contribute to the place he grew up in.

If there's a Torontonian inclined to speak poorly of Ed, I've yet to make their acquaintance. I'm sure he pissed someone off: he was a businessman and a success, which requires some steel and ruthlessness. But whatever bad karma he may have kicked into motion he more than made up for with his turkey give-aways and cheerful, deliberately low-rent star schmoozing. He insisted he was just one of the regular people, even as he blew a fortune attempting to make downtown Toronto the Canadian "Great White Way." And no-one doubted him because, well, he obviously was who he was.

And just who is shedding tears on behalf of Conrad? Hard to say, though there are Canada Post writers who will talk about what a treat it was to work for him. I don't doubt it. In his inevitably massive way Conrad Black attempted to be an "Honest Ed" on behalf of the entire nation by throwing his considerable clout into breaking the hegemony of Toronto's national newspaper. While he was at it, he took a vigorous stab at keeping Canada's oldest magazine alive, as well. Personally, I thought it was all great fun -- the country needed this hubris-driven craziness. Pierre Elliott Trudeau pulled it off, but he had to dip deep into the people's purse; if the free-market really is superior to all that, why couldn't an unfettered capitalist achieve a visibly public legacy similar in scale?

But you can only hemorrhage money on such an enterprise for so long before your interests are distracted by something flashier, like becoming a Lord. And pissing off that gnarled toad in the PMO. And writing a laudatory biography of Richard M. Nixon that sits at 1148 pages.

Black lost my sympathies somewhere down that road. It could have been that smirk on his face while he wore those funny clothes, I dunno .... But whatever he's guilty of, I'm sure it's incredibly big, because Black isn't a person who does anything on a small scale.

And yet today's headlines somehow do make him seem smaller, like the ex-husband who's finally lost his fortune and his arm-candy. If only he'd stuck to Canada, maybe we'd still love him.

Ed Mirvish, 1914-2007: a guy who knew how to contribute to the place he grew up in.

Thursday, July 12, 2007

Obligatory U-20 World Cup Posting

I've been watching a bit of the FIFA U-20 World Cup broadcasts. I'm not enough of a football (aka "soccer") fan to get much from these games. As my father the hockey player and San Jose Sharks fan once said after returning to the prairies and watching his first Manitoba Moose game, "If you're an NHL fan, you tend to see the mistakes."

So it is with U-20 and those of us who, like myself, are nominal FIFA fans. The kids have a lot of spirit and no lack of talent ... but you tend to see the mistakes.

HOWEVER, you do also see aspects that impress, specifically a general revulsion among the U-20 set for cry-baby antics that might, just might, lead to a penalty for the opposing team. None of this, "My ankle! Your shoelace touched it!! GAH! I need the stretcher! Coach, strap me in!!!"

Yes, if you look hard enough you will find signs of hope flourishing among the younger generation.

So it is with U-20 and those of us who, like myself, are nominal FIFA fans. The kids have a lot of spirit and no lack of talent ... but you tend to see the mistakes.

HOWEVER, you do also see aspects that impress, specifically a general revulsion among the U-20 set for cry-baby antics that might, just might, lead to a penalty for the opposing team. None of this, "My ankle! Your shoelace touched it!! GAH! I need the stretcher! Coach, strap me in!!!"

Yes, if you look hard enough you will find signs of hope flourishing among the younger generation.

Tuesday, July 10, 2007

Once Harry Retires

Our family is gearing up for the summer trip across North Superior to Winnipeg. My wife and I think it's a spectacular journey, and even the girls have internalized the rhythm of two long days' worth of driving. There was a time when playing DVDs for them was a must; now they wouldn't think of it.

The biggest trial will be deciding what we listen to ... or rather, how often the parents can endure listening to the Flushed Away soundtrack. Last year the soundtrack was Joseph & The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. But things worked out rather well because we borrowed the first two Harry Potter books on CD from the library.

It may be that driving across the Canadian landscape while possessed by a desperate desire to avoid hearing Donny Osmond crow, "Anyone from anywhere can make it if they get a lucky break!!" is the ideal environment for a guy like me get wild about Harry. Certainly performance artist Jim Dale deserves an Emmy for his reading. And I've been informed that as the books get longer, Harry's adolescent indecisiveness becomes a bit tedious. But I've gotta admit: Rowling knows how to hook a reader.

This was something I'd been told back when the books were still fresh. My sister in law said (with some concern) that Harry Potter was the only fiction her son was interested in. It's a common chorus, especially when it comes to boys. Harry Potter is cleanly-written escapist prose, well-designed to deliver harrowing thrills. But with Harry retiring, where can young (and aging) readers turn to ease their Potter jones?

Toronto's national newspaper cobbled together a panel to answer this question, and they came up with this. Some interesting titles are suggested, and every seller's urge seems to be fantasy, fantasy, fantasy. This strikes me as slightly wrong-headed, as does the suggestion that older Harry readers pick up The World According To Garp. Were I to approach my (now young adult) nephew with a copy of Garp, he'd be as likely to read it as he would Portnoy's Complaint, or any other musty chestnut from the 70s.

Not that the 70s aren't fertile ground for literary thrill-seekers. My first post-Potter recommendation would be William Goldman's Marathon Man. It's breathless fantasy built to deliver a maximum surprise factor. And its narrative arc isn't dissimilar to Harry's: orphaned Thomas Levy plugs away as a history geek, unaware that his older brother is a deadly secret agent who is about to awaken Thomas' own capacity for subterfuge and death-dealing. Well, alright: there are some differences in scale. Three pages of "Is it safe?" before Szell pulls out the drill and gets to work on a fresh nerve is a level of sadism that Dudley Dursley only dreams of. But it's a tough book for a guy in late adolescence to put down, which is what we're after. It's even got a sequel (a strange one, to be sure, but still entertaining). Now if Goldman could just be persuaded to write a few more books and make it a series, we'd be talking about a genuine literary marathon.

The biggest trial will be deciding what we listen to ... or rather, how often the parents can endure listening to the Flushed Away soundtrack. Last year the soundtrack was Joseph & The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. But things worked out rather well because we borrowed the first two Harry Potter books on CD from the library.

It may be that driving across the Canadian landscape while possessed by a desperate desire to avoid hearing Donny Osmond crow, "Anyone from anywhere can make it if they get a lucky break!!" is the ideal environment for a guy like me get wild about Harry. Certainly performance artist Jim Dale deserves an Emmy for his reading. And I've been informed that as the books get longer, Harry's adolescent indecisiveness becomes a bit tedious. But I've gotta admit: Rowling knows how to hook a reader.

This was something I'd been told back when the books were still fresh. My sister in law said (with some concern) that Harry Potter was the only fiction her son was interested in. It's a common chorus, especially when it comes to boys. Harry Potter is cleanly-written escapist prose, well-designed to deliver harrowing thrills. But with Harry retiring, where can young (and aging) readers turn to ease their Potter jones?

Toronto's national newspaper cobbled together a panel to answer this question, and they came up with this. Some interesting titles are suggested, and every seller's urge seems to be fantasy, fantasy, fantasy. This strikes me as slightly wrong-headed, as does the suggestion that older Harry readers pick up The World According To Garp. Were I to approach my (now young adult) nephew with a copy of Garp, he'd be as likely to read it as he would Portnoy's Complaint, or any other musty chestnut from the 70s.

Not that the 70s aren't fertile ground for literary thrill-seekers. My first post-Potter recommendation would be William Goldman's Marathon Man. It's breathless fantasy built to deliver a maximum surprise factor. And its narrative arc isn't dissimilar to Harry's: orphaned Thomas Levy plugs away as a history geek, unaware that his older brother is a deadly secret agent who is about to awaken Thomas' own capacity for subterfuge and death-dealing. Well, alright: there are some differences in scale. Three pages of "Is it safe?" before Szell pulls out the drill and gets to work on a fresh nerve is a level of sadism that Dudley Dursley only dreams of. But it's a tough book for a guy in late adolescence to put down, which is what we're after. It's even got a sequel (a strange one, to be sure, but still entertaining). Now if Goldman could just be persuaded to write a few more books and make it a series, we'd be talking about a genuine literary marathon.

Wednesday, July 04, 2007

People of Darkness by Tony Hillerman

I finished my first Tony Hillerman mystery — a Jim Chee novel, People of Darkness. I enjoyed it, and at some future date I'll likely go back to the Hillerman shelf for more. Hillerman writes a sturdy mystery; People of Darkness would make an excellent discussion point for any first-year fiction workshop. The standard mystery-thriller elements are present and accounted for: a mysterious wealthy man desirous to have his McGuffin returned to him, a series of inexplicable deaths, an “engineer” (a professional hit-man unaccustomed to seeing his work screwed up) and a lone-wolf lawman who has to nut it all out before he's killed in an avalanche of violence triggered by greed.

Pro “reviewers” occasionally roll their eyes at such unadorned narrative tent-posts, but identifiable elements are integral to every story and good writers (and their editors) have a sense of which “tricks” to employ to keep the reader turning pages. Hillerman's stunt is to approach the whole mess from the point of view of a Navajo Indian. In this novel, Hillerman's protagonist (Chee) solves the case while doing a little mulling over an inner conflict of his own: should he further embrace the White Man's world by training with the FBI, or should he proceed with the more intricate Navajo rites of passage? Hillerman paints a persuasive picture of an Indian approaching a White Man's crime and using an Indian world-view to bring one small corner of his world back into balance.

Hillerman's characterization is respectful and not a little romantic — he freely admits in his memoirs that he was charmed by the Navajo point of view thanks to two Navajo shipmates returning with him from the war in Europe. The skeptic in me wonders if Navajos aren't as prone as other Indian tribes to the pitfalls of substance abuse and despair. It could be they aren't; it could also be this is something Hillerman touches on in other books. James Lee Burke certainly doesn't address the height and breadth of all Louisiana's evils in a single Dave Robicheaux novel (even though the rage in his prose suggests that's a very real temptation), and George Pelecanos, as ambitious an ego as one could hope to find in an author, is canny enough to parcel out his city's issues one novel at a time.

Pelecanos is worth mentioning, because Hillerman (and Burke) can rightly claim to have paved the way for him. Half of Pelecanos' protagonists are Greek (Pelecanos' background), the other half are black (not Pelecanos' background). It takes a certain level of fearlessness to explore “the other”: racial, cultural, sexual, religious — any other. Hillerman took pains to explore with sensitivity, and I look forward to reading more of his work.

Pro “reviewers” occasionally roll their eyes at such unadorned narrative tent-posts, but identifiable elements are integral to every story and good writers (and their editors) have a sense of which “tricks” to employ to keep the reader turning pages. Hillerman's stunt is to approach the whole mess from the point of view of a Navajo Indian. In this novel, Hillerman's protagonist (Chee) solves the case while doing a little mulling over an inner conflict of his own: should he further embrace the White Man's world by training with the FBI, or should he proceed with the more intricate Navajo rites of passage? Hillerman paints a persuasive picture of an Indian approaching a White Man's crime and using an Indian world-view to bring one small corner of his world back into balance.

Hillerman's characterization is respectful and not a little romantic — he freely admits in his memoirs that he was charmed by the Navajo point of view thanks to two Navajo shipmates returning with him from the war in Europe. The skeptic in me wonders if Navajos aren't as prone as other Indian tribes to the pitfalls of substance abuse and despair. It could be they aren't; it could also be this is something Hillerman touches on in other books. James Lee Burke certainly doesn't address the height and breadth of all Louisiana's evils in a single Dave Robicheaux novel (even though the rage in his prose suggests that's a very real temptation), and George Pelecanos, as ambitious an ego as one could hope to find in an author, is canny enough to parcel out his city's issues one novel at a time.

Pelecanos is worth mentioning, because Hillerman (and Burke) can rightly claim to have paved the way for him. Half of Pelecanos' protagonists are Greek (Pelecanos' background), the other half are black (not Pelecanos' background). It takes a certain level of fearlessness to explore “the other”: racial, cultural, sexual, religious — any other. Hillerman took pains to explore with sensitivity, and I look forward to reading more of his work.